KOH KER

(928 - 944)

PRASAT NEANG KAO, KOH KER (928-944)

KOH KER

(928 - 944)

PRASAT NEANG KAO, KOH KER (928-944)

The following eleven slides are arranged to simulate the carefully staged sequence of views which would unfold as a visitor approached Jayavarman IV's forest capital, Koh Ker. This 7km by 5km site, 120km northeast of Angkor contains nearly 100 shrines similar to this classic version of the single, cella Khmer prasat aedicule or module. While the east door (at front) is open, the north, west and south doors are blind, similar to the ones pictured later in the 1st or inner enclosure of Prasat Thom. This shrine has been nicknamed "The Blue Lady" because chemicals in the laterite used to build it not only harden when exposed to air but also turn indigo. The shrine is one of the last on the road leading from Angkor to Prasat Thom, the state temple complex at Koh Ker.

Despite its unprecedented grandiosity, the temple complex of Prasat Thom ("Great Temple") proved just a parenthesis in the history of Angkor and its empire. It was built and abandoned in under twenty years, a testimony to the ambitions but limited vision of Jayavarman IV, its sponsor. He was a contender for the Khmer crown upon the death of his brother-in-law,Yashovarman I, around 915, an example of how the Khmer succession was frequently claimed by the male relatives of a former king's mother. He was finally declared chakravartin or "universal ruler" only after contesting the brief reigns of Harshovarman I (915- 923) and Isanavarman (923-928,) in whose deaths he probably played a part. He had already begun building an alternative capital on his extensive landholdings northeast of Angkor, where he may have retreated after being driven from the court by Yashovarman I's sons. The scale of the site seems intended to compensate in masonry for his tenuous legitimacy and to lay a foundation in brick for a new dynasty.

Jayavarman IV's state temple, Prasat Thom, covers an unprecedentedly long, 800m "liturgical axis" which strings the standard features of a Khmer “temple mountain” in a linear, scenographic sequence rather than a unified concentric structure with the shrine at its center. For example, it contains both a central shrine and, beyond it, a second grander temple mountain or prang, the only seven-tier pyramid in Khmer architecture. If that were not sufficient, it was punctuated by an upper shrine containing a 5m tall Shiva linga. Prasat Thom's impressive "processional path" or ceremonial way" is unusual in more respects than length: it is skewed from northeast to southwest, like an arrow aimed squarely at the previous capital, Angkor.

SITE PLAN, KOH KER (928 - 944)

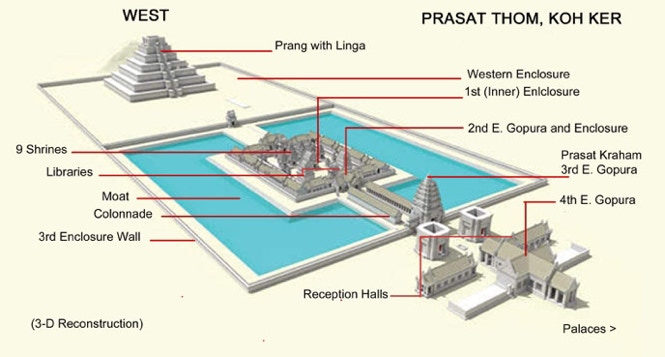

The complex essentially has four enclosures. The outer or 4th lacks a continuous enclosure wall, consisting on the east of a large, cruciform gopura, two lateral receptions halls, and a pair of shrines flanking the east-west axis. This is balanced on the west, by a large enclosure containing the prang tacked onto the rear of the 3rd enclosure. The monumental 3rd east gopura, Prasat Kraham, leads to a causeway which crosses a moat to an artificial island containing the 1st and 2nd enclosures. The narrow 2nd enclosure is lined almost entirely with "service buildings," an anticipation of the continuous galleries of future Khmer temple mountains. The small 1st enclosure is packed with libraries and no fewer than nine Shiva shrines.

THE "PALACES," PRASAT THOM,

KOH KER (928-944)

The "liturgical axis" at Prasat Thom begins some distance to the east of the 4th east gopura with two buildings of the type conventionally referred to as "palaces," also found in the outer enclosures of Preah Vihear (11th Century) and Phimai (c.1100) and believed to have provided housing for visiting dignitaries. Since these three temples are outside Angkor, those dignitaries would presumably have been imperial officials. At Angkor, the North and South Khleangs may have served a similar function for foreign ambassadors. At Koh Ker, the palaces consist of four rectangular buildings around a courtyard, similar to those at Preah Vihear’s 3rd north gopura.

PRASAT KRAHAM AND COLONNADE

PRASAT THOM, KOH KER (928-944)

4TH EAST GOPURA, PRASAT THOM, KOH KER (928-944)

The cruciform 4th east gopura has affinities with the 4th and 3rd gopuras at Preah Vihear, a temple also far from Angkor on an escarpment near the Thai border which has a similarly protracted liturgical axis and reception buildings adjacent to its gopuras. At Koh Ker, the template and holes to hold a stucco pediment are all that remain, as well as, an atypically narrow lintel with hardly enough room for floral swags beneath its garland and at its center what seems to be a figure, probably Garuda, with two addorsed heads beside it, most likely nagas.The gopura connects to "reception galleries" on either side, as well as the two shrines in front to the monumental 3rd east gopura.

The 3rd east gopura is taller and larger than the central shrine (though not, of course, the prang.) Hence, it was a shrine in its own right named Prasat Kraham, the "Red Temple." Its lintel is also atypical because the garland sprouts from two warriors facing each other with a missing figure between them, either Sunda, Upasunda and Tilottama or Shiva and Arjuna, both scenes from the Mahabharata. The prasat is seen here from the west, looking back from the 2nd enclosure down the collapsed double colonnade (both sides of which were roofed) lining the causeway across the moat to the artificial island. Today the moat between the 3rd and 2nd enclosures is a pond filled with waterlilies. The remnants of the 3rd enclosure wall surrounding it are visible at the left (below.)

MOAT, PRASAT THOM, KOH KER (928-944)

The 1st enclosure at Prasat Thom suffers from Jayavarman IV's tendency towards over-compensation. It is crammed with the two mandatory libraries, a very large mandapa, twelve small shrines and a platform or plinth with nine Shiva shrines (another record for Khmer architecture.) The central shrine in the front row of five presumably contained the primary garbagriha and linga, though it is no larger than the rest and inconsequential compared with the prang looming behind it. This photo shows the backs of the two shrines behind the central one which has a thatched roof while it is being restored. The shrines’ blind, west doors, with a column where they would otherwise have opened, are similar to those at East Mebon (953) and Pre Rup (961) – the two temples built immediately after Rajendravarman (944-968) returned the capital to Angkor. These two at Koh Ker would, presumably, have been covered with stucco not incised sandstone like those later shrines.

From the 1st and 2nd enclosures, a causeway continued west back across the moat, through the small 3rd west gopura into the prang's enclosure which is larger than the other three enclosures combined. The pyramid with seven tiers, the largest number of any Khmer structure, sits not at the center but against the enclosure's western wall; its size and location are clearly designed to make it the true focus and climax of the "liturgical axis." Thus, the diminutive Shiva shrine in the cramped 1st enclosure is revealed as just a foil for the prang's monumental isolation and Jayavarman IV's devaraja, his 5m personal linga beyond and above all the Shiva's lingas below.

1ST ENCLOSURE, PRASAT THOM,

KOH KER (928-944)

The "liturgical axis" at Koh Ker maps a linear sense of time contrary to traditional Hindu and Khmer cyclical temporality. This finds spatial expression in a temple's organization as a passage from the profane world through concentric enclosures of increasing sanctity to the divinity at its center; then returning, through the temple's decidedly anti-climactic western half to secular or historic time. The west, associated with death and the female principle, corresponds with the "dissolution phase" of Hindu chronometrics, (outlined in appendix II,) the return to primal prakriti or formless matter, a world without dharma, purusha, or Brahman, ushering in a kali yuga and Shiva Nataraja or Vishnu as Kalki's destruction of the universe – until, after a not inconsiderable pause, a new satya or kriti yuga ushers in a Golden Age of innocence and saintliness. Prasat Thom's dramaturgy, instead, plots a line but not one leading endlessly into the future; instead, it punctuates the east-west axis at the foot of the pyramid celebrating Jayavarman IV’s accession to the Khmer throne. This is as far as the king was concerned and as far as he intended his subjects to think; "après moi le deluge."

PRANG OR PYRAMID, PRASAT THOM, KOH KER (928-944)

The west face of the prang or pyramid resembles a natural rock formation. It lacks a staircase; the only access was originally from the east, the climax of the "processional path" or axis leading across the entire site from the "palaces" on the east (see the reconstruction of the Prasat Thom site plan above.) This was the ne plus ultra, the point beyond which there was no point going. The 7th or topmost terrace now lacks a shrine; if it had one, it would have needed to be tall enough to hold a 5m linga with platforms at the top to anoint it with ritual ghee, a considerable engineering feat. One tradition suggests that the terrace was not topped by a linga, but a statue of Shiva Nataraja with ten arms and five heads dancing the tandava, the destruction of the cosmos at the end of a mahayuga. In either case, it seems an over-obvious assertion of Jayavarman IV's power and rightful possession of the illusive devaraja as current chakravartin or "lord of the universe," (a title, it should be noted, merely denoting that he had won victories in all four cardinal directions).

WEST FACE, PRANG, PRASAT THOM, KOH KER (928-944)

From the 7th terrace, the view (below) to the southwest faces pointedly towards Mt. Kulen (actually a plateau) where Jayavaraman II instituted the devaraja cult of Khmer kingship in 802 and, beyond that, Angkor, the former and future capital.

7TH TERRACE, PRANG, PRASAT THOM, KOH KER (928-944)

THE INTERNATIONAL TRAFFICKING IN KHMER ANTIQUITIES

Sculpture at Koh Ker participated in the same gigantism (some might say megalomania) which marked the rest of Jayavarman IV's remote empire; (it is difficult to resist comparison with another larger-than-life-size figure in his jungle retreat, Marlon Brando's imposing presence in Apocalypse Now, based on Kurz in Conrad's Heart of Darkness.) The three sculptures below were looted, despite their size and weight, from an unusual figure group originally at Prasat Chen, an out-lying temple of the Koh Ker group. The figure on the left, depicts Bhima, the second and strongest of the Pandava brothers, who with the aid of Krishna killed one hundred of his Kauvara kinsmen, including, the heretofore invincible Duryodhana, chief instigator of the Pandavas' exile and hence of the Kurukshetra War, the central narrative in the Mahabharata. The other two figures, identified only as "kneeling attendants," include a monkey, often the allies of humans, for example, Hanuman and Surgiva in the Ramayana. Historians hypothesize that they may represent the indigenous "hill tribes" who seemed "primitive" and "sub-human" to the Indo-Aryans but whose support was essential in their ultimate conquest of the Dravidians, heretofore the indigenes’ overlords.

When, in 1978, the Vietnamese drove the Khmer Rouge into remote regions such as Koh Ker, Pol Pot and his remaining court financed their last-ditch stand by selling the national patrimony to prominent museums and collectors in Europe and America, something the EFEO and former French colonial administration actively discouraged. (The first "Conservator d'Angkor," Jean Commaille, is thought to have been murdered in 1916 by smugglers frustrated by his strict embargo on the antiquities trade.) When the Khmer Rouge were finally driven into refuges along the Thai border (paid for by the U.N., the U.S. and China), these became crossing points for contraband smuggled out of the country during the chaos following, the three-year genocide. The new Cambodian government put in place by the Vietnamese lacked the means to provide basic public services and security, let alone patrol remote temples, many of which had been heavily mined so that venturing there required a substantial incentive. This was provided by well-informed antiquities dealers in Bangkok who placed "orders" for specific valuable pieces of Khmer sculpture with their Cambodian surrogates.

A well-established supply chain, obvious to anyone familiar with Khmer antiquities, spirited a glut of artifacts from the "killing fields" of Cambodia through middle-men in Bangkok and Singapore to reputable galleries and auction houses in London, Zurich, New York and Tokyo, and from there into the hands of major museums and collectors. For example, the sculptural group from Prasat Chen was only grudgingly returned by the Norton Simon Museum in Los Angeles, the Cleveland Museum and the Metropolitan Museum in New York after the publication of irrefutable evidence by the Cambodian authorities of their illicit provenance. The trade in stolen antiquities continued long after the Khmer Rouge was routed, most famously in 1999, when jackhammers and a circular saw were used to slice an 11 square meter section of a widely admired bas relief of the bodhisattva Lokeshvara from a wall at Banteay Chhmar, a major, though remote, temple near the Thai border. The truck carrying the wall, now cut into 117 pieces to facilitate "fencing" such a well-documented work, was intercepted at the Poipet border crossing to Thailand. Less egregious examples continue to find their way into the catalogs of leading auction houses and the mantelpieces of Asian art collectors.

49