PHNOM

RUNG

(1113 - 1120)

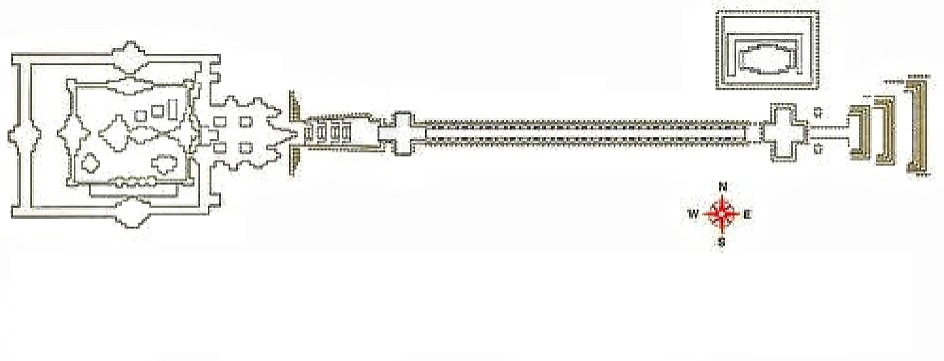

PROCESSIONAL WAY, PHNOM RUNG (1113 -1120)

PHNOM

RUNG

(1113 - 1120)

PROCESSIONAL WAY, PHNOM RUNG (1113 -1120)

Phnom Rung was the last, "mountain temple" built by the Khmer, joining Phnom Bakheng (907) Phnom Bok and Phnom Krom, also foundations of Yashovarman I (889 - 915,) and Preah Vihear (11th and 12th Centuries.) As with Preah Vihear and Phimai (c.1100,) the temple immediately preceding it in this survey of Khmer temples, the following photos are arranged to simulate the experience of a visitor proceeding down its unusually extended liturgical or east-west axis.

Phnom Rung is located at the cone of an extinct volcano in the same Dangrek Range as Preah Vihear, 188 km to the east, on the road north from Angkor to Phimai, 131 km north of the capital. It bears such close stylistic similarities with the latter, slightly earlier temple, it seems likely many of the same artisans worked on it. Phnom Rung, like Phimai, appears to have built on the site of an earlier shrine dating from the reign of Suryavarman I (1002 -1049) which was incorporated into a radically new, more ambitious monastic foundation soon after Suryavarman II’s rise to power in 1113. The site of this major Khmer temple, now in Thailand, testifies to the continuing influence of the northern Mahidharapura dynasty, introduced by Jayavarman VI in c. 1080.

Unlike Phimai, Phnom Rung is neither a Buddhist nor royal foundation; instead, it was built by a relative and general of Suryavarman II who had been awarded the territory on which the temple stands. Late in life, this military leader decided to retire to the life of a Saivite ascetic (though hardly a wandering sadhu) and established an order of "rishi," wise men or monks, around himself. Accordingly, Shiva is prominent in his many manifestations on the lintels and pediments of the temple whose mountaintop location was meant to evoke not Mt. Meru but Mt. Kailasa, the Himalayan peak believed to be where that god led his austere, repentant life as Bhikshatana. Since this order's founder returned to military life on occasion, it may also have had a martial component such as the Grail and Teutonic Knights and Japanese sohei, the warrior monks of competing Tendai sects.

This view above, west from the top of the three monumental staircases to the cruciform terrace at the beginning of a 160m processional way, shows the first of three naga bridges at its far end and five flights of stairs beyond it rising to the temple's two enclosures above. In the absence of a 3rd enclosure, the processional path is lined with 67 lotus bud stelae or sema, boundary markers. A "palace" or guest house is located to the north outside the temple precinct. It seems likely that the height and position of the central tower or prang in the distance was determined so its distinctive ogive or convex outline, first seen at Phimai, would be fully visible from the beginning of the processional path.

2

11

11

12

14

10

15

9

7

6

5

4

3

1

8

1. Entrance staircase

2. Phlab Phla – palaces

3. Ceremonial way with sema stones

4. 1st naga bridge and terrace

5. Primary staircase

6. Terrace with four ponds

7. 2nd naga bridge and terrace

8. East face, 2nd enclosure

9. 1st and 2nd east gopura

10. 3rd naga bridge and terrace

11. Principle shrine and tower

12. Ancillary shrine

13. Pran Nol (earlier shrine)

14. Library

15. Laterite building

SITE PLAN, PHNOM RUNG (1113 -1120)

Phnom Rung's site plan stretches along an upward-sloping natural ridge, illustrating an extreme case of "linear expansion" or "aedicular addition," like Koh Ker or Preah Vihear, where a temple's parts are strung along a processional path punctuated by terraces, staircases and gopuras, so that, in contrast with the contraction seen at Kandariya Mahadeva, Phnom Rung projects the temple's sacred space deep into the surrounding countryside. Its conventionally east-facing shrine is placed inside two, concentric enclosures 500m above the foot of the three monumental eastern staircases. This liturgical axis crosses three naga or rainbow bridges in the form of cruciform terraces in its course, symbolically representing steps in the ascent from the profane to sacred: 1) before the five staircase at the end of the processional way; 2) in front of the 2nd enclosure and 2nd east gopura at their top; 3) between the 1st east gopura and the shrine's ardhamandapa or eastern porch.

On the east, the 1st and 2nd gopuras and their enclosure walls merge, so that, in effect, the 1st enclosure is entered directly from the naga terrace with its four ponds before it. This is consistent with the diminishing role of 2nd enclosures, observed as early as Koh Ker (928-944) and then at East Mebon and Pre Rup. possibly consequent to the declining importance attached to the so-called "service buildings" (whatever their exact function) and their incorporation into galleries acting as enclosure walls. The 1st enclosure at Phnom Rung has the same linearly-extended concatenation – ardhamandapa > mandapa > antarala > garbagriha/shikhara seen at Phimai, as well as two libraries and the casual scattering of sub-shrines from different periods, including the older Prang Noi shrine.

The 1st naga bridge and terrace are in the foreground of the view at left, back east along the processional way.. The northern and southern stairways to cruciform naga terraces were probably added merely for symmetry since they would give access to the processional way or ”liturgical axis” from unhallowed ground beyond the boundary markers which substitute for enclosure walls along the long approach to the 1st and 2nd enclosures at “mountain temples” like Phnom Rung and Preah Vihear. The need to follow a prescribed, paved route with no “short-cuts” was imperative for preparation to see the god in his shrine. Indeed, in the absence of any evidence of a pradakshina path, the extended Khmer processional paths through gopuras, enclosures, causeways, terraces and naga bridges may have substituted for the standard Hindu ritual of parikrama for which there is no evidence at any Khmer site.

1ST NAGA BRIDGE AND TERRACE, PHNOM RUNG (1113 -1120)

The photograph, above, was taken from the top of the five flights of stairs, at right, leading from the ceremonial way and 1st cruciform naga terrace (visible at the lower right) to the four cruciform ponds and 2nd naga bridge before the 2nd and 1st enclosures on the ridge above. These formidable stairs find an equivalent in the monolithic, four-tier embankment before the 3rd north gopura at Preah Vihear but they have been refined by division into two-part tiers of continuous moldings, as found at the Baphuon. The persistence at Preah Vihear of gopuras to enclosures which had only one side seems to have been dropped at Phnom Rung in favor of passages over rainbow naga bridges and physical and spiritual ascent up staircases.

EAST FACE, 2ND ENCLOSURE, PHNOM RUNG (1113 -1120)

The full breadth of the 2nd (outer) east gopura and gallery appears only upon reaching the top of the five flights of steps from the first naga bridge and terrace. The gopura might be described as a triple, staggered shala, indicated by its three descending levels, the lowest of which is elongated into a gallery, punctuated by two corner blocks, the same pattern seen in the extension of the Baphuon's three terraces and at Phimai. The 1st enclosure substitutes a wall for a gallery on its east which is functionally superfluous since it abuts the 2nd enclosure's gallery so closely. The symmetry of the façade's bays is broken by the introduction of a third blind window on its south range and extra porch on its north.

2ND NAGA BRIDGE AND TERRACE, PHNOM RUNG (1113 -1120)

Four pools, thought to represent the sacred rivers of India or seven oceans around Mt. Meru, precede the 2nd enclosure as they do the 1st at Phimai. They symbolize an advance closer to the home of the god and the sacred center and cella, as does the 2nd naga bridge and terrace visible beyond them, leading to the 2nd and 1st east gopuras and the central shrine. They may have suggested the four "pools" of the "cruciform cloister" of the 1st terrace of Angkor Wat with the notable difference that there they are included inside the fabric of the building and the naga bridge and monumental five flight staircase is replaced by the three flights of stairs to the 2nd terrace. These pools and those at Phimai may, in turn, have been suggested by the more convincing passage over the four quadrant moat surrounding the 1st enclosure at nearby Prasat Hin Muang Tam which preceded them.

The 3rd and smallest naga bridge and cruciform terrace, at right, links the ardhamandapa or eastern porch of the prasat (left right in the photograph) to the conjoint gopuras of the 1st and 2nd enclosures (right.) Again, it marks the threshold between a lower and higher degree of divinity and the progression towards a more enlightened level of consciousness. The theme of rebirth in a state free of samsaric defilements is echoed by the lintel in the photograph below which faced worshipers as they approached the ardhamandapa from this naga bridge.

3RD NAGA BRIDGE AND TERRACE, 1ST ENCLOSURE, PHNOM RUNG (1113 -1120)

This invites observations on the role of the naga in Khmer myth and theology in general. In the three, monotheistic, Mosaic religions, the serpent is anathematized as a symbol of the demonic, duplicitous, bestial and immediate cause of humanity's "Fall." There is, in fact, physiological evidence of an instinctive, adrenal "spike" in response to movements resembling a snake's in many primate species, including humans, which may be traced back to their arboreal origins. The Khmer, in contrast, saw these venomous creatures as generally auspicious and sacred, based on their association of snakes with the liquid element as mediating or flowing between earth and heaven, as a purifying place of rebirth, most notably in their invention of the rainbow naga bridge, as at Phnom Rung, but also curling around the torana arches of their pediments literally against the sky. This may hearken back to the belief that the world originated from springs deep within mountains, associated with the womb and the garbagriha ("womb chamber,") a chthonic strain in Khmer religion predating the importation of the Vedic "sky" deities.

A similar association was made independently by Mesoamericans where it took the form of the "Cloudy Serpent" or Milky Way which they saw as wrapping itself around the universe. This notion also reared its hood in the figure of Quetzalcoatl, the flying "Feathered Serpent" worshiped by the Toltecs and post-Classical Maya, (who pronounced it “K’uk’ulkan.”) Khmer garlands issuing from nagas and their cousins, makaras or sea serpents, also find a counterpart in the "speech scrolls" and “vision serpents” of Mesoamerican deities. The Greeks also endowed snakes with powers of prophecy and healing; the Delphic Python or oracle, whose mother was Gaia/Ge, the earth goddess/mother herself, was destroyed by the sun god, Apollo, equivalent to the Vedic Surya, symbolizing the triumph of the sky gods over their chthonic predecessors. Apollo’s son Asclepius inherited or recuperated the serpents’ healing power in his rod entwined with non-venomous snakes which remains a symbol of the medical profession. Snakes also slithered across the floor of his sanctuary at Epidaurus where diseases were diagnosed by the understandably anxious dreams of the patients sleeping there.

The pediment at right from the eastern porch leading into the shrine shows a ten-armed Shiva Nataraja, or "Lord of the Dance," whose tandava destroys the decadent world devoid of dharma at the end of each mahakalpa. The same scene appears in the same position at Phimai and represents nirvana, the annihilation or release of the self. Accordingly, the lintel in partial shadow under it, depicts the Hindu creation (or recreation) myth, the birth of Brahma, the creator of the next world from a lotus bud growing from the navel of Vishnu, as he sleeps in the Ocean of Milk on the naga, Shesha or Ananta, "endless." The serpent may be related to an ouroboros, a snake biting its own tale, emblematic of the Hindus' cyclical rather than linear view of time. It refers more directly to the the 3rd and final naga bridge, symbol of rebirth, directly in front of it. On the left of the lintel are paired parrots and at the upper right two copulating monkeys, rare in generally prudish Khmer art but perhaps excused because the simian could represent the animal side of human reproduction. (This important lintel was bought from a notorious antiquities broker by the Art Institute of Chicago which was eventually compelled to return it to its original location here.)

EAST PEDIMENT, EASTERN PORCH, PHNOM RUNG (1113 -1120)

SOUTHERN FACE, MANDAPA, PHNOM RUNG (1113 -1120)

The central tower at Phnom Rung is very similar to the one at Phimai and anticipates the profile of Angkor Wat. It has double porches, each half-emerged, the outer with an open window, the inner with a "blind," baluster, each surmounted by a gable and pediment. The inner porch is treated like the mandapa with a slightly projecting, side half-story and full, first story which supports the pediment and has its own eaves. This adds two rathas to the nine at Phimai (including the portal, analyzed in figure 4 of the introduction;) the added rathas are reflected by indentations in the adhisthana moldings. (This makes eleven rathas per quadrant, exceeding the normal limit of navaratha seen at Phimai.) A third pediment borne on corbels (not pilasters) is attached to the “cross-on-square” projection of the shrine, filling the area between the top of the inner porch's gable and the varandika or entablature of the shrine.

The southern face of the shikhara features a cascade of seven pediments, as at Phimai, three above the double porches and one representing these on each of the four aedicular tiers or levels. The pediment over the outer porch shows Shiva at "royal ease" (with one foot dangling from his cushion) surrounded by rishis. The third pediment over the portal to the sanctuary, shows Sa god enthroned, and borne by what seem like geese, swans or peacocks (hence, Brahma, Saraswati and Skanda, respectively.) The first of the four aedicular shikhara pediments features Yama, god of the south and of death, on his bullock in a niche shaped like a mandorla, "almond" (or naga's hood.) The level above shows Shiva in a hemispheric niche, possibly a cave, with two rishis or hermits; the 3rd level, again represents Shiva, here on Nandi; on the 4th and final tier, Shiva is shown meditating, while the tower is capped by a lotus bud.

Phnom Rung’s mandapa is divided in five parts horizontally. It has a barely-emerged central, double porch with pilasters, next to which are two equal wings with one baluster window each; these are framed by the antarala on the left (west) and ardhamandapa on the right (east.) Vertically, it has three cornices, eaves and pediments: the lower, a "minor order," corresponds with the level of the eaves over the aisles or half-story projecting from the mandapa, as well as, the base of the pediment of the portal to the antarala; the second, a "major order," continues the line of the cornice and eaves of the antarala, ardhamandapa and the mandapa's "full story;" the third, follows the eaves of the "aedicular," (compressed) second story roof over the mandapa (corresponding with the upper lobe of a split valabhi shrine or gavaksha of which the mandapa's eaves would be the lower. This is also parallel with the pediment above the point where the antarala's roof intersects the wall of the shrine, acting as kind of sukanasa. It is also at the level of the pediments above the shrine's north, west and south double porches; these lack pilasters, lintels or portals but continue the cascade of toranas over what would otherwise be a gap between the gable of the inner porches' pediments.

The lower pediment above the outer porch of the mandapa’s south portal is badly damaged but suggests a bull with two riders, presumably an Umamahasvara, that is the Great God/Shiva, his consort Uma/Parvati and his mount Nandi, surrounded by attendants bearing parasols and fly whisks of honor. The second pediment is covered by the first and the upper, third pediment shows Rama and Lakshmana wrestling with the giant Virada, a rakasha or demon living in the Dandaka forest, who briefly captured, Sita, while she loyally shared her husband's exile there, prefiguring her subsequent abduction by Ravana, the central action of the epic. Unlike Phimai, the antarala has a low door with its own pediment which has been interpreted as Krishna lifting Mt. Govardhan.

SOUTHERN PORCH AND SHIKHARA, PHNOM RUNG (1113-1120)

MOLDINGS, SOUTHEAST CORNER, SHRINE, PHNOM RUNG (1113-1120)

The moldings of the adhisthana (base,) jangha (walls,) pilasters, friezes and cornices throughout Phnom Rung are noted for their finely incised floral motifs and scrollwork. Since similar carving appears on the "tree of life" pediments found on the nearby, older Prang Noi sub-shrine, they may reflect a regional style. The decoration, pictured above, tends to consist of rows of repeated patterns; self-contained, they seem static, as if marking off divisions or sections of the mural surface, emphasizing the zones of the wall and avoiding the dynamic but eliding motion of the converging and diverging vines of an arabesque or floral scroll. Since these decorative bands seem to repeat self-contained plaques or designs, their carving could have been facilitated by the use of standardized molds or templates.

TYMPANUM AND LINTEL, WESTERN PORCH, PHNOM RUNG (1113-1120)

The tympanum above from the western porch of the sanctuary at Phnom Rung shows a scene from the Ramayana in which Rama's wife, Sita, is flown by monkeys to witness a battle in which Rama appears to have been killed (in fact, an illusion created by the sorcerer, Ravana, in the hope of weakening Sita's resistance to his advances.) Sita is borne in a palace which looks similar to the shrine of which it is a part. Comparison can also be made with Kubera, the god of wealth's, pushpaka vimana, one of the ratna or jewels emerging from the "Churning of the Ocean of Milk,” stolen by his half-brother, Ravana, and returned by Rama. Its appearance here demonstrates that the convention of representing gods traveling to earth in "flying palaces" was still in used 500 years after its first appearance on the walls of the southern group of octagonal shrines at Sambor Prei Kuk (Isanapura) between 600 and 650. The crudely carved lintel under it shows a second episode from the Ramayana where Indrajit, Ravana's son, ensnares Rama and his loyal brother, Lakshmana by turning his arrows into in a nagapasa or net of snakes; the two are later released with the help of Hanuman, one of whose exploits is pictured above it. The same scene is depicted at Phimai on the lintel of the west portal of the mandapa.

61