PREAH

PITHU

12th - 14th

Centuries

TEMPLE X FROM TEMPLE U, PREAH PITHU (12TH – 14TH CENTURIES)

PREAH

PITHU

12th - 14th

Centuries

TEMPLE X FROM TEMPLE U, PREAH PITHU (12TH – 14TH CENTURIES)

The Preah Pithu group of five temples is one of the most picturesque, yet least frequented, areas of the Angkor Archaeological Park, even though it is located just north of the Victory Square, the ceremonial center of Angkor Thom. The archaeologists of the EFEO, with a surprising lack of Gallic éclat, named the five temples prosaically Temples T, U, V, X and Y, perhaps one reason they are so often overlooked. The ensemble was never intended to be a group and dates from the Angkor Wat period possibly to near the abandonment of Angkor in 1431. The four Hindu temples, T, U, V and Y can be linked stylistically to Angkor Wat, the fifth,Temple X, is Buddhist and could date to as late as the early 15th Century. All five temples are in an advanced state of dilapidation but some retain well-carved bas reliefs. Today they occupy a tranquil, wooded setting interspersed with ponds depending on the season.

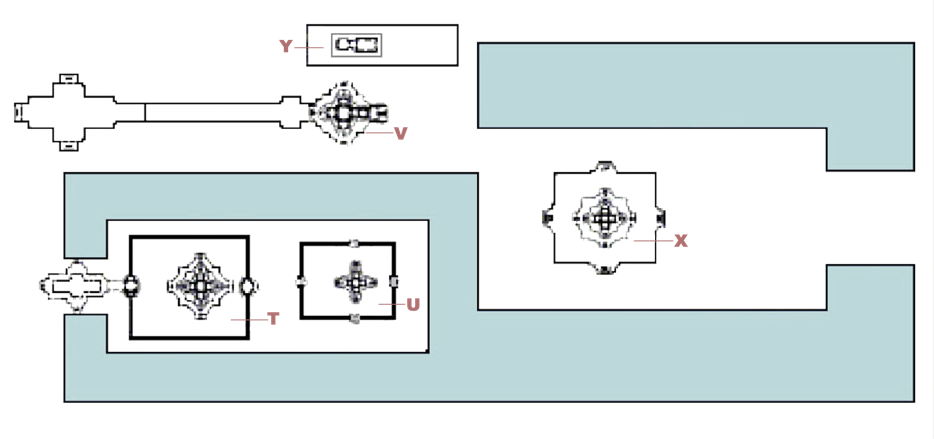

SITE PLAN, PREAH PITHU (12TH – 14TH CENTURIES)

Temples T and U seem conceived as a pair since they occupy the same east-west axis and Temple U can only be accessed through Temple T. Temple T is approached by a causeway with a naga bridge, like those at Chao Say Tevoda and Banteay Samre, which crosses a moat surrounding both temples. The causeway connects them on the west to the Victory Square and cardo, the main north-south street of Angkor Thom and highway from Angkor Wat past the Bayon and the Elephant Terrace on to Preah Khan. Both have their own enclosures and both are uncharacteristically set off to the east, like Angkor Wat, indicating they were west-facing temples. In this respect, they resemble the twelve Prasats Suor Prat towers, immediately to their south.

Temple X appears to have been almost entirely surrounded by a later extension of that moat and is connected to temples V and Y by just an isthmus at its northwest corner. Temple V, the largest shrine, lacks an enclosure wall and faces east, preceded by a double porch and placed on an imposing plinth. Nonetheless, its primary approach is from the west, along a 70m long causeway with a naga terrace, running the length of Temples T and U combined and ending at the same north-south highway through Angkor Thom. Finally, Temple Y is perched on a low ridge north of Temple V; its cella or sanctuary is on axis with those of Temples V and U. It has a large mandapa, connected by an indented antarala to its garbagriha, but no enclosure wall or jagati (plinth or stereobate.)

TEMPLE T, PREAH PITHU (12TH CENTURY)

This view from the south near the northernmost Prasat Suor Prat in the Victory Square of Angkor Thom, shows the moat (foreground,) the eastern enclosure wall around temple T, as well as the small eastern gopura (right) leading to Temple U. Although, as mentioned, the temple is set back to the east in its enclosure and the causeway leads to the west-facing shrine, a linga was found in its 3m square cella, indicating a dedication to Shiva. Thus its west-facing orientation cannot be ascribed to its dedication to Vishnu, as "Lord of the West," as has Angkor Wat's, but demonstrates instead that the Khmer would violate convention for convenience, as at Preah Vihear, since the logical approach to this island temple is from the highway to its west. Nonetheless, at Temple V, a more imposing causeway also leads from the west but the temple faces east.

Temple T, seen, above, looking up its principal western steps towards the door frame, all that remains of its entrance porch, presents in miniature the profile of the Khmer "temple mountain" in its classic form. It rises neither precipitously nor hesitantly over three tiers of modulated moldings, though the conventions of Indian temple architecture are a distant memory and adapted to the Khmer taste for greater simplicity and clarity. The shrine itself is a simple Greek cross, a square cella with four partially-emerged porches; the central square is not redented nor do the porches have redented portals. The sides of the porches also have no windows but niches with apsaras; if there were also dvarapalas none remain.

PREAH PITHU, TEMPLE U (13TH CENTURY)

Temple U, to Temple T's east, is considerably smaller, also cruciform, but retains more of its sculptural ornamentation. It sits on a single elevated jagati or stereobate which flows directly into the pitha or adisthana (base) of the cella and its porches. Here there are dvarapalas, as well as, the pairs of devatas or apsaras who frame the windows of the porches. The south-facing lintel showing Shiva Nataraja is clearly visible in the photo above; other lintels include the Trimurti and "The Churning of the Ocean of Milk." The shrine displays a polychromy, similar to that at Preah Khan and Banteay Kdei which along with stylistic details of its lintels suggest a later date for its construction than Temple T.

SHIVA NATARAJA, SOUTH LINTEL, TEMPLE U, PREAH PITHU (11TH CENTURY)

“THE CHURNING OF THE OCEAN OF MILK,” SAMUDRA MANTHAN, WEST LINTEL, TEMPLE U, PREAH PITHU (11TH CENTURY)

The south-facing lintel shows a ten-armed Shiva Nataraja, or “Lord of the Dance,” dancing the tandava, the destruction of the universe at the end of each mahayuga (or mahakalpa depending on the chronometric used, see appendix II,) after all dharma or divine purpose has left a corrupt world. Appropriately, he stands on the head of a kala or kirtimukha, a "face of glory," an apotropaic symbol, here portrayed atypically with his lower jaw which, in the myth, he lost when Shiva forced him to eat himself. He grasps two leogryphs, lion-like creatures or chinthes, with hands directly connected with his mouth, which in turn sprouts the traditional garland with inward-curling volutes but outward at its ends and without the usual nagas or makaras. To Shiva's proper right, the god with four faces (his fourth is behind,) is Brahma who will create a new universe once Shiva has destroyed the old. On Shiva’s proper left, is his consort, Parvati, who will dance the gentle laysa. Among the swags of foliage hanging from the garland, beside Brahma, is Shiva and Parvati's son, the elephant-headed, tubby Ganesha, as well as his opposites, the ascetics usually associated with the god in his aspect as Bhikshantana, "divine mendicant". Curiously, both Ganesha and Brahma lost a head when Shiva severed them in a rage, hence, perhaps his role as penitent.

The Samudra Manthan was the Hindu myth most frequently depicted by the Khmer because it symbolizes the immortality and joy which results from unity in following dharma, the divine design for life. Here the traditional garland issuing from the mouth of a kala has been replaced by the naga, Vasuki, whom the devas and asuras are twisting to churn the ocean. In this version, Vishnu straddles the sea snake, though in its usual telling, he used Mt. Mandara as a pivot braced on his Mesozoic or reptilian, second incarnation as the slow-moving tortoise, Kurma, (a symbol for the earth in many cultures, including Mesoamerican.) A one-headed elephant is shown above Kurma, who would normally represent Ganesha, Shiva's son, except he plays no part in this myth. He might, instead, represent one of the fourteen ratnas or jewels which were by-products of the churning, in addition to amrita, the elixir of immortality and its ultimate goal, specifically, Airavata, the three-headed elephant and vehicle of Indra, the King of the Gods, pictured on the South Gate and Elephant Terrace of Angkor Thom; but what happened to the other heads? To the left, the woman might be Lakshmi, the related, goddess of prosperity, another ratna, who became Vishnu's consort. Or she could represent an apsara or celestial nymph ubiquitous in Khmer art, who also rose, like Venus Anadyomene, from the churning of the ocean. Behind Kurma, is yet another ratna, the seven-headed horse Uchhaihshravsas, like the elephant shown here in short-hand with just one head, who would become the vahana or "vehicle" of Surya, the Vedic sun god. The figure on the right might represent Dhavantari, yet another ratna, the god of ayurvedic medicine and vaidya or physician to the devas. If so, he would be holding the jar of amrita but his prominent belly, if holding a jar of money, suggests he might represent Kubera, whose appetite for wealth, like a hedge fund billionaire's, was insatiable. As in many Bayon period lintels, the traditional garland, kala and makaras have been almost entirely eliminated by narrative details; as a result, they lack the continuous curves and clear rhythmic swags which unify the classic Khmer lintels of the 9th and 10th Centuries.

TEMPLE X, PREAH PITHU (TAQ 1431)

A date in the 14th or 15h Century for Temple X is based both on the in-tact Buddhas in niches surrounding its cella, which suggests the temple may not have existed during the reign of the Hindu iconoclast, Jayavarman VIII (1243-1295,) as well as on the temple’s unfinished state which might be a consequence of the removal of the capital from Angkor to Phnom Penh in 1431. The temple is also, uncharacteristically, slightly off-axis which could testify to a decline in Khmer surveying; in any case, the temple was clearly built after Temples T and U and their moat.

Despite Temple X's conjectural, late date and Buddhist affiliation, it still adheres to the basic Khmer shrine or prasat module (or "aedicule.") Not only does it resemble Temple T, which may have been built two hundred years earlier, it is not that different from the corner towers on the upper terrace of Ta Keo (c. 1000,) one of the first Khmer shrines with fully-emerged porches. It shares with them a dramatically elevated pedestal with three steep terraces and an unbroken staircase and is pancharatha, with five vertical projections, if one includes with these, as is conventional, the pronounced fronton of applied pilasters, lintel and pediment. Although these are now missing at Temple X, a comparison with those at Preah Palilay and Temple U might suggest what they were like.

As at Temple T, its three tiers of moldings are united by a repeated sequence which is easier to see in this photo. The basic elements have family resemblances with the standard repertory of Hindu temple moldings – inward-curving khumba foot moldings, convex kumuda, pointed karnika and, broad, flat pattika bands or filets. Every sequence of moldings in a Hindu temple whether in the base or adhisthana, wall or jangha or superstructure tends to repeat in miniature the basic divisions of the shrine as a whole – vyalamala, joists, vedi, balustrade or half-wall, gala, habitable recess, and kapota, eave. In contrast, at Temple X, the moldings within each tier tend to repeat each other in reverse order across a prominent, flat, though incised central course, e.g. 1,2,3,4,3,2,1 (the number of moldings will variy depending on how the components or sub-moldings of each are counted.) Even at this late date, the masons were careful to preserve the regularity of each sequence, though they have made the sequences symmetrical rather than aedicular, in keeping with Khmer taste; as a result, the different moldings have become more a pattern while losing their figurative references.

TEMPLE V, PREAH PITHU (13TH CENTURY)

The garbagriha or cella of Temple V is aligned to the north across the moat from the sanctuary of Temple U. On its west is a 70m causeway and naga terrace running the length of Temples T and U over which most people would presumably have approached the temple. Yet, unlike temples T and U, Temple V is east-facing, raised on a high plinth and entered by this imposing eastern staircase, similar to those at Temple X and T. Therefore worshippers would presumably have clambered down the hillside beside the moat, then climbed back up the steps following the liturgical axis; arrival by water, at least for the most distinguished visitors, can never be ruled out because so little of Angkor's extensive network of canals has been mapped.

Temple V's shrine, at 4m square, is the largest of any garbagriha in the Preah Pithu group, while, in addition to its four porches, it has vestibules or outer porches; perhaps a more ambitious linearly-expanded shrine was contemplated though there are no gopuras or enclosure walls. Its long causeway may suggest a mountain temple like Preah Vihear or Phnom Rung leading to a crest (here just a modest hill) and temple. At Temple V, however, the direction of the shrine is reversed so it doesn't face the causeway but juts out like the prow of a ship over the abyss. The liturgical axis does not come from the west as the climax of the causeway or top of the rise, but out of space, above the stairs and moat below, not a human entry but, perhaps, a runway for the morning sun and gods to touch down from Mt. Meru.

SOUTH FACE, TEMPLE Y, PREAH PITHU (13TH CENTURY)

Temple Y is located on a ridge to the north of Temple V. with its cella or garbagriha parallel to the axes of Temples U and V. It consists of a shrine (left) with an antarala, vestibule or joint (center,) connecting it with a large mandapa (right,) in fact, the largest single chamber of any in the Preah Pithu group. There are no remnants of an eastern porch, portal, steps or even a front wall. Like Temple V it opens onto space or more precisely, forest; it seems unlikely that it was meant simply to be an open shed. The antarala is atypical with two half and one full pediment, as if one had been folded; its door opens onto the plinth or jagati and it leads to both the garbagriha and mandapa, as if it might have been intended as the main entrance. If so it would be unique in Khmer temple architecture; it seems more likely that the portal and eastern porch are missing or were left unfinished.

PEDIMENTS, TEMPLE Y, PREAH PTHU ( 13TH CENTURY)

The full pediment over the antarala's door (above) is taken from the Ramayana and shows the battle between Sugriva and his older brother, Valin or Vali, king of the Vanara monkey kingdom. Surgriva thinking his brother had been killed by a demon, assumed his kingship; when Vali reappeared, he exiled his brother and married his wife. In his forest habitat, represented here in Khmer convention by a single tree, Sugriva met Rama, (the seventh avatar of Vishnu,) who had also been exiled to the Dandaka forest for fourteen years by his wicked stepmother. While there, he too had lost his loyal wife, Sita, who was abducted by the demon king of Lanka, Ravana. Sugriva and Rama agreed to become allies; the Ramayana is structured around such parallels which reinforce its primary concern the nature of legitimate kingship. When Sugriva challenged Valin to single combat, they were evenly matched, until Rama hiding in a bush shot an arrow through Valin's heart, (it what might seem a peculiar example of chivalric values.) Sugriva and his counselor, Hanuman, the monkey general, then played a decisive role in the Battle of Lanka which succeeded in recovering Sita, (though Rama, again rather ungallantly required she endure a fire ritual to prove her fidelity while the captive of Ravana.) The monkeys at the pediment's base may be spectators but seem dejected; mourning the death of Valin, (who was not without reason for his enmity towards Surgriva) was a frequently depicted theme in Khmer art, showing empathy with an honorable but defeated adversary. Some ethnographers have argued that Rama's monkeys allies represent a mythic memory of hunter/gatherer aboriginal hill tribes with whom the Aryans may have allied themselves against the Dravidian kingdoms then dominating the sub-continent, who would therefore be associated with Ravana and his demons.

The subject of the half-pediment (above) is from the other Hindu epic, the Mahabharata, a parallel scene of single combat, between Krishna, (the ninth and penultimate avatar of Vishnu, pictured triumphant at top) representing the human ideal, and the thousand-armed, demon king of Bali, Bana or Banasura. The location of both the twenty-armed Ravana and Bana's realms testifies to the early prevalence of trade across the Bay of Bengal, through the Straits of Malacca to Bali and on to Funan and Chenla, the states which probably eventually became Angkor. Bana's strength derived from his devotion to Shiva for whom his thousand arms beat the kohl or mridanga, the drum or damaru for the god's tandava or "dance of destruction" at the end of each epoch. In return, Shiva granted him a boon rendering him invincible.When his daughter, Usha, fell in love with Krishna's son, Aniruddha, Bana imprisoned him leading to his combat with Krishna, pictured here. Krishna was about to kill the asura but instead severed all but two of his arms at the behest of Shiva, honoring the god's oath to Bana. Bana apologized to Krishna and Usha and Aniruddha wed. The incident has been interpreted as illustrating Krishna's respect for dharma or divine law, here the inviolability in feudal cultures of a ruler's "troth" or pledge.

Again, there is a clear parallel, elsewhere in the epic, when Krishna explains to Arjuna in the seminal "Bhagavad Gita" that he must not allow kinship to inhibit his slaughter of his half-brothers, the Kauravas, because they had violated dharma by denying his brother, Yudishthira, his rightful succession to the throne. As with Ravana and his asura subjects in the Ramayana, Bana's kingdom likely represents the Aryan's' traditional enemies, the Dravidians, whose states occupied the Gangetic plain and Deccan at the time of the Indo-European migration (c.2000 – 1500 B.C.E.) The Khmer often depicted their rivals, the Cham, as asuras. The myth has also been seen as a call for mutual respect between Saivites and Vaishnavites, the two main sects of Hinduism, especially valued by the Khmer, as seen both in the hybrid deity, Harihara, and the murals of the 2nd Terrace at the Bayon.

76