The Form of Emptiness

and the “Emptiness of Form”

It remains conjectural, in the absence of any explicit theological program, such as that depicted on the walls and balustrades of Borobudur’s five terraces, whether the “virtual terraces,” edges, galleries, gopuras and thresholds along Preah Khan’s east-west “liturgical axis” marked significant stages on a monk’s path to enlightenment and his attainment of the ten Mahayana paramitas, perfections or insights, necessary to become a bodhisattva, Nonetheless, a monk, like today’s visitors, would pass more than 20 limens or “thresholds” in the course of crossing just these three enclosures; the succession of gates and doors along this “pilgrim’s progress” would frame an unobstructed view from the profane space of the 4th enclosure on the east, to its counterpart on the west and beyond, the forest around Preah Khan. The Buddha image in the cella would be barely visible, though it marked the point where the two cardinal axes of the terrestrial plane intersect the vertical axis of spiritual ascent vanishing at the tip of the shikhara or summit of Mt. Meru, into formless space; in a literal sense, then, the “vanishing point.” From here, the bodhicitta, who had advanced far on the path to enlightenment, might perceive the statue, the shrine, the temple and the world beyond, even his perceiving them, as maya, just thoughts and hence illusions. The series of empty doors in all four directions would frame sunyata or emptiness, stretching to infinity, while the concentric structures would be like echoes of the primal A-U-M, just reverberations. Paradoxically, the closer the adept approaches the realization that “form is emptiness,” represented by the emptiness at the void at the temple’s center, the statue of Buddha who himself achieved nirvana or non-existence, the more the architecture, its diamonds, rectangles, dimensions and alignments dematerialize and become mere reminders of their own lack of independent existence or origination. Might this help explain, in part, the architectural anti-climax and axial slackening of Jayavarman’s VII’s Buddhist complexes compared with the monumental massifs at the centers of the Baphuon or Angkor Wat?

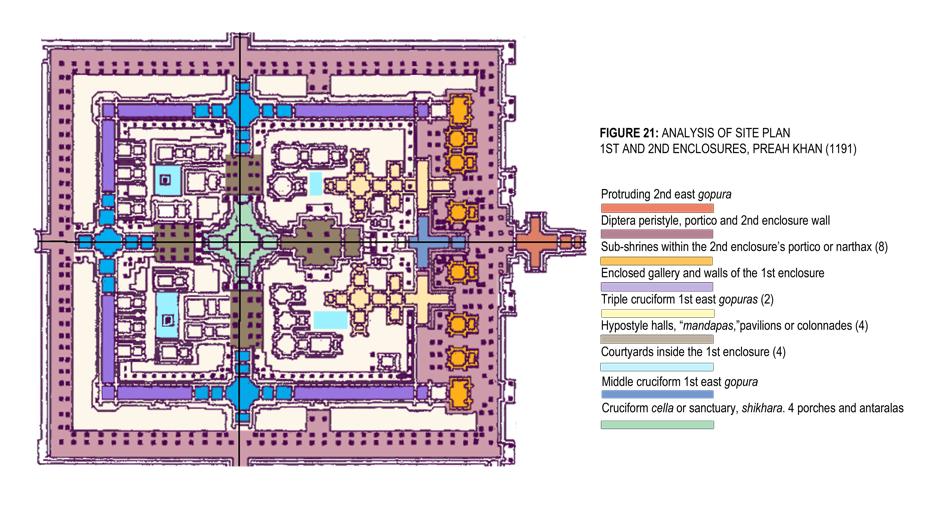

In addition to its three ancillary shrines or sub-temples and the “Hall of Dancers,” the 3rd enclosure contains five buildings, three terraces and five pools which appear to have been added without symmetrical equivalents or an overall plan and may have been constructed later than the temple as the need arose. These reverse a clear tendency in Khmer architecture from the Bakong to Angkor Wat to incorporate all the temple’s part in a single coherent structure. In contrast, this fissiparous clinamen or centrifugal force, which the eminent Angkorian scholar, Maurice Glaize, described as the “spirit of confusion” of Jayavarman VII’s architectural initiatives, achieves its most exuberant expression in the 1st and 2nd (4,3) enclosures of Preah Khan. The temple seems to flout the classical canon, so recently established at Angkor Wat, with an almost Mannerist insouciance and delight in novelty. As an example, the cruciform, Latin cross 2nd east gopura (red in figure 21,) the liturgically privileged entrance to the 2nd enclosure, is not embedded in its gallery but stands proud of it, merely tangent on its west. This might be because the gallery in which its crossbar would normally have been embedded is here replaced by a diptera (two-column-wide) peristyle (maroon) which might be charming, if it didn’t face the blind walls of the 1st enclosure’s gallery (purple,) in effect, a colonnade around the back of a building. Even this unpromising architectural idea is compromised on the east where this peristyle dissolves into a cluttered narthex, full of columns straying among eight, free-standing shrines (orange.) In place of a distinct 1st enclosure wall with gopuras clearly marking the east-west processional path, two square corner chambers (purple, discussed at the bottom of pg. 30,) and three arms of two cruciform gopuras (yellow) jut into this clogged “narthax.” Only on second glance can one deduce that these are parts of the 1st enclosure’s eastern gallery, which our easily distracted architect never bothered to connect. The two (yellow) gopuras’ western arms are not, as one might expect, portals into the 1st enclosure, rather they become the eastern arms of a second cruciform structure whose crossbar is three chambers wide and whose western arm again becomes the eastern arm of a third, even more elaborate cruciform structure with a redented cella and double porches on its three outer sides; not content with this, two additional shrines dangle like earrings from it, framing the east-west axis. This ensemble (yellow) could be read as three overlapping cruciform gopuras or one upright with three crossbars, one, three and five chambers wide. This replication is only arrested by a similar proliferation of shrines in the 1st enclosure’s eastern half.

The middle of the three 1st east gopuras (slate blue) has both east and west porches; the latter opens on the space between the “earrings” and a single-column pteron that runs around the inside of the 1st enclosure’s windowless gallery, too narrow to walk on and abandoned altogether on its west for a row of seven more shrines; the consequence of honoring 515 manifestations of emptiness is, ironically, clutter. The east-west axis next continues through two chambers, more like airlocks, into a hall shaped like a shallow Greek cross with four pillars and two aisles (brown,) in what seems an allusion to a mandapa. An indentation on its west serves as the antarala to the eastern porch of the central shrine’s cruciform sanctuary (light green,) smaller than its gopuras. (Much more striking examples of this reversal between entrance and entered can be found in the “temple cities” of Tamil Nadu, such as the Meenankshi Amman in Madurai and Sri Ranganathaswamy in Srirangam.) The cella’s three other porches give onto short, half-hearted, open colonnades or faux-mandapas (brown,) three or four columns wide, no more than filler linking the shrine, the errant pteron and the overbearing 1st north, west and south gopuras (bright blue) whose redented central spaces project four chambers laterally and three axially for a total of eight each. Like the superfluous peristyle (maroon) and the pteron, the three colonnades (brown) face the backs of more shrines clumped together into four irregular courtyards (light blue.) On the east, these are the spaces left between the two tripled gopuras (yellow) and two L-shaped agglutinations of shrines, leaving barely enough room to squeeze through to a forgotten shrine wedged into the enclosure’s southeast corner. On the west, more assorted shrines form the sides of two more courtyards (light blue) with pillars at their centers, probably used as altars or balipithas which sit athwart the diagonals from the central shrine to the 1st and 2nd enclosures’ western corners.

One of the striking features of Preah Khan is the slackening of axial momentum approaching its anti-climactic central shrine (14, light green,) an aedicule of Mt. Meru in a temple itself a replica of this summit of the Hindu universe, which has here become lost among its foothills. The temple’s liturgical path strays among its prolix shrines and digressive colonnades before it can reach its modest point. Gopuras protrude in front of or intrude into enclosures, blurring their boundaries. Galleries, peristyles and colonnades don’t so much define as seep space on which a plethora of random shrines coagulate forming cramped courtyards while rendering the enclosure’s gallery and pteron superfluous. The clear axial and lateral branching of galleries and gopuras into a matrix of alternating positive and negative spaces at the Baphuon and Angkor Wat,dissolves at Preah Khan in a morass of masonry, where monks – and modern visitors – could easily lose their sense of a center. A similar phenomena was noted at another Buddhist temple, Borobudur in section V, but there pilgrims could follow their progress towards their final goal through the narrative on its twisting walls.

Preah Khan does not seem to have been planned so much as happened, adding theological and architectural ideas whenever they inspired its sponsors over four decades. The lack of a coherent blueprint, however, need not have been a flaw so much as a choice whose point may have been the lack of one, so that one could keep proliferating and emanating many possibilities. Thus, the absence of a rigid spatial hierarchy might reflect not a defect, but a desire to be dis-placed, to lose one’s egocentric sense of “territoriality” for a diffused “Buddha consciousness” – everywhere and therefore nowhere – capable of seeing the temple’s bewildering plethora of shrines as a unity, even if a unity of illusion. Therefore what has been disparaged as Jayavarman VII’s “improvisations” and horror vacui may not have been unintended but a cultivated “confusion” designed to counter the dualism implicit in the notion of a center and periphery, here and there, self and non-self. In Vajrayana visualization, outlined at the beginning of this section, someone with siddhi powers does not start with a mandala in mind but elaborates one, afresh and unpremeditated every time, since its invention is the sadhana or meditative practice and each one an illusion to be erased. Would it be surprising if an architecture which believed “form was emptiness” would be empty of form? In this light, Preah Khan seems ideally designed to accommodate the fluid Buddhism which appears to have developed at Angkor during Jayavarman VII’s reign, far from the institutionalized centers of the religion, such as the university at Nalanda (Bihar) or the Theravada sangha of the Mahavihara at Anuradhpura (Sri Lanka.) In this respect, the king may have been following Buddha’s advice to find your own way to enlightenment, more in keeping with the antinomian tradition of “forest monks” and Hindu sadhus than ordained priests or monastic glossists. On the other hand Jayavarman VII’s penchant for building vast institutions would seem to place him clearly in the camp of the “Conventuals” rather than the “Spirituals” in the Franciscan schism. The challenging paradox for architecture of articulating a theology for which ultimate reality was without spatial extension or form and of creating structures which could express the uncreated, sunyata or emptiness, may have been addressed more directly and systematically at Jayavarman VII’s own temple mountain, the Bayon, the last and most idiosyncratic built at Angkor and the subject of the next section.

Cruciform cella or sanctuary, shikhara. 4 porches and antaralas