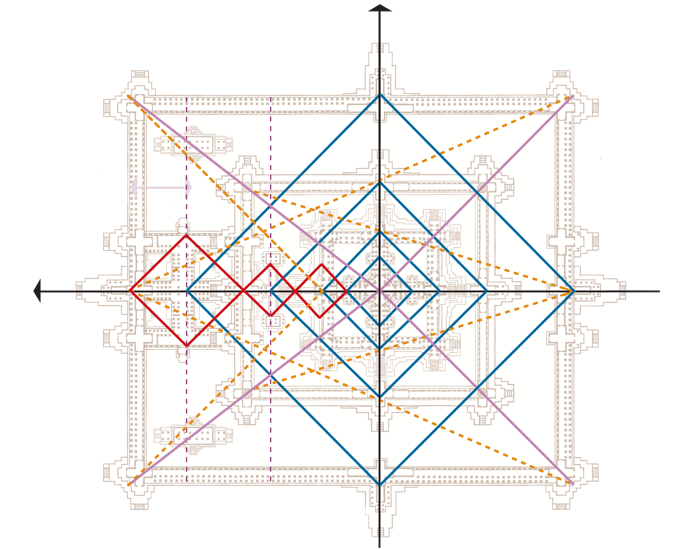

FOR A KEY TO THE COLORED LINES, SEE THE TEXT

IN THE PARAGRAPHS BELOW.

FIGURE 18: ANALYSIS OF LINKAGES BETWEEN ANGKOR WAT’S THREE TERRACES

Angkor Wat’s asymmetrical western and symmetrical eastern sides are sewn into a unified architectural fabric by a web of diagonal lines, visual threads connecting its gopuras, galleries, towers and cruciform structures, which weave together these two opposed geometries.The gradual passage from the profane world beyond the temple to the sacred, symmetrical space of the 3rd terrace is made visible not only through visual alignments but by motifs, structures and proportions repeated at different scales which lend coherence to its carefully calculated discordant dimensions. These diagonals cut across the temple’s rigid orthogonals – the seemingly endless galleries and lateral diversions most visitors probably followed on their protracted, indirect path back and forth across the liturgical axis – and mark their zig zag progress across the temple’s matrix. Some of these “laces” tying the temple together are traced in figure 18.

1) Lines (purple) drawn from the four corners of the 1st terrace to the central tower position the eight corner towers of the 2nd and 3rd terraces around it, forming a double panchayatana or quincunx (a chiastic or X-shaped arrangement of five, and here, nine objects.) Because of the asymmetry of the eastward offset, these lines form a right angle east of the north-south axis but an acute angle to its west; they also pass through the centers of the two libraries on the 1st terrace.

2) Three pairs of diagonals (broken orange lines) link key points across all three terraces: (a) lines drawn from the 1st terrace’s eastern corners cut through the 2nd north and south gopuras and meet at the middle 3rd west triple gopura; (b) a vector from the middle 3rd east triple gopura (the midpoint of the eastern edge of the 1st gallery and terrace) passes through the 1st north and south gopuras of the 3rd terrace and reaches the western corner towers of the 2nd gallery and terrace; (c) two diagonals drawn from the western corners of the 1st gallery and terrace (the 3rd or outer enclosure,) cut the northwest and southwest corners of the two libraries of the 1st terrace and the northeast and southeast corners of those of the 2nd terrace, meeting at the midpoint of the western edge of the 3rd gallery and terrace, the 1st west gopura.

3) Four concentric diamonds (blue lines) centered around the principal shrine and tower can be constructed by connecting the intersections of the cardinal axes with the northern, southern and eastern outer edges of (a) the 1st (b) the 2nd and (c) the 3rd galleries, as well as (d) the centers of the four “cruciform pavilions” (3, in figure 17) inside the 3rd terrace’s colonnades. The western vertices of diamonds (a) (b) and (c) fall on the midpoints of the “threshold lines” (10, 11) of the 1st and 2nd terraces and the western colonnade of the square 3rd terrace.

4) These four diamonds are interwoven with a chain of three smaller diamonds (red lines:) (a) the first is inscribed in the “cruciform cloister” between the midpoints of its four edges; (b) its diagonals, if extended, then cross until they reach the “threshold line” (10) of the 2nd terrace which falls along the outer edges of the “cruciform walkway’s” northern and southern arms and then turn back to meet at the end of that walkway’s eastern arm, the western edge of the protruding 3rd terrace’s lip; (c) from there, the lines cross again until they intersect the western edge of the 3rd gallery and terrace where they switch back to join at the center of the western cruciform pavilion (3) forming a third red diamond;(d) they then would cross and become coincident with the fourth or innermost concentric diamond (blue) around the central shrine.

The asymmetries of Angkor Wat resulting from the insertion of the cruciform “cloister” and “walkway” have the effect of increasing the number of thresholds and the number of possible lateral paths to follow. The network of interlocking diamonds may have acted to draw visitors through one self-contained cruciform structure into the next and hence provided an axial momentum to counteract the lateral divagations of the galleries, cloister and walkway athwart the “liturgical axis” to the central shrine. Once past the 1st “threshold line,” int the sacred space of the 9x9-pada paramasayika mandala, the linked smaller diamonds (red) which outline the “cruciform cloister” and “walkway” are interwoven with the four concentric diamonds (blue) until they become coincident with the innermost diamond around the central shrine. The shrine is itself a redented or “stepped” diamond holding the cult statue of Vishnu, (today preserved in the gallery of the outermost or 4th enclosure.) Visitors may sense the tightening of the asymmetry of the 1st and 2nd terraces, marked as they pass the two crosswalks at the threshold lines (11,10) and the contraction of the seven intertwined diamonds into the coincident symmetry around the central shrine and shikhara.

At Angkor Wat, movement along the liturgical, east-west axis could not have been intended to be strictly axial but must have been lateral as well, more like that at Borobudur than at the Bakong. Why else would the 1st and 2nd galleries exist and why would the 1st have been so lavishly embellished with bas relief? Each cruciform structure offers an alternative to axial progress which would prolong and perhaps preclude a visitor’s progress to the 3rd terrace and its shrine. Pradakshina or clockwise (solar) circumambulation is the usual preparatory ritual at Hindu temples for supplicants before they view the woken god and so receive its darshan. Such a corkscrew “processional path” might involve various forms of puja or reverence – prayers, recitations of mantras, rosaries, offerings and meditations. We know what lined Angkor Wat’s 1st gallery – narrative bas relief murals – but in the cruciform cloister and 2nd and 3rd galleries there is no evidence of sub-shrines nor of additional murals as at the Bayon or panel reliefs as at the Baphuon. After two Thai sacks and the abandonment of Angkor in 1431, the re-consecrated Theravada Buddhist wat was famous for having one thousand Buddha shrines in its galleries; these are presently exhibited in the central hall of the National Museum in Siem Reap. There is no indication at any Angkorian site that circumambulation was practiced there, so the purposes of these galleries must remain a mystery. The asymmetries resulting from the insertion of the cruciform “cloister” and “walkway” did increase the number of thresholds and possible structures to circumambulate; they might equally have served as places to congregate like the mandapas attached to the garbagriha of “linearly expanded” temples, such as Phimai or Thommanon, constructed at roughly the same time. They are, however, clearly not intended to provide a place to gather before the cella at the center of the 3rd terrace; not only are they too far away but they actually divert visitors from the direct liturgical path. Diversion may, in fact, have been their purpose since it is quite likely that access to the central shrine was not an option for many of those coming to the temple. The central shrine and its connecting galleries are too small to have contained more than a fraction of the visitors who could be accommodated in Angkor Wat’s other vast spaces. The 3rd terrace may have been restricted to a select group of brahmins, nobles or initiates; for the rest, the galleries and cloisters would have been the endpoint of their visit.

Angkor Wat in Context

Angkor Wat illustrates the differences between “aedicular expansion” as practiced in India and “aedicular projection” in Khmer architecture and helps to account for their contrasting interpretations of the “temple mountain,” the question which launched this introduction, in figure 1. The Indian solution for expanding temples and the number of deities they could accommodate, as we have seen, was to build the shrine’s shikhara out of tiers of miniature replicas or aedicules of itself and other shrines. At Angkor, in contrast, these tiers are projected around the central shrine, a largely unchanging Khmer prasat; their sides become long galleries embellished with bas reliefs which join full-size or near-full-size copies of the central shrine and shikhara, which could be thought of as antefixes or acroteria at their corners. Thus, the Khmer temple mountain does not simply rise above the central shrine but around it and beneath it. The central shrine and its shikhara become an aedicule, even finial,or kalasha or stupi of the temple mountain or pyramid on which they rest. The temple's terraces are not miniaturized but magnified, unlike the stepped, aedicular tiers of the shrine's own shikhara. Finally, both the shrine and “temple mountain” are “aedicules” or miniaturized simulacra of Mt. Meru, an original existing only as an idea and ideal of the mind.

If Angkor Wats’ towers, gopuras and the galleries linking them were not projected but contracted, they would resemble the talas of a Dravida vimana with its aedicules or shrines joined by a hara or “necklace”of notional (applied, arpita galleries, as at the Dharmaraja Ratha in figure 8. If the double panchayatana or quincunx of towers at Angkor Wat were retracted still further, so these towers emerged only half-way from the central shrine and tower, crushing the galleries between them, they might approximate a Nagara or Northern Indian sekhari temple with two ranks of urushringas descending along the diagonals of its single tower, analogous to the four urushringas at the cardinal points of the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple, in figures 6 and 7.Thus the “temple mountain” at Angkor could be seen as resulting from a process of aedicular magnification and projection rather than one of contraction and accretion.

Angkor Wat might also be compared with the largest concentration of “temples mountains” anywhere – the more than 3000 ku or gu (Pali > guha cave) and zedi or chedi, temples and stupas, at Bagan in Myanmar. If Angkor Wat’s first two terraces were not separated but stacked above each other with the central tower and shikhara rising from their top, the resulting profile might resemble the double cubes crowned by “corncob” towers of two-story temples like the Gawdawpalin (1227, at right;) if its 3rd terrace were added, it would resemble the only triple-story temple at Bagan, the Thissa-wadi (1334.) At Bagan, the galleries of temples are not projected away from the central shrine, as at Angkor, or placed above it in tiers, as in India, but internalized within the shrine itself as one and sometimes two tall, barrel-vaulted, concentric corridors around either a solid or hollow core containing the primary Buddha image(s.) These corridors are not lined with outward-facing bas relief but frescoed with inward-facing murals depicting the jatakas or “birth stories” of the Buddha’s 547 prior incarnations, shrines carved or painted with scenes from Buddha’s life or ranks of hundreds of identical Buddha statues displaying the standard mudras, reminiscent of those at Borobudur in figure 10. This allows an exponential increase in the number of shrines, images and therefore the darshan or Buddhist merit the temple can accommodate and dispense to its sponsor and its worshippers. These corridors, often 15m high, greatly extend the pradakshina or circumambulatory path around the primary Buddha image or images, contrasting starkly with the dark, narrow passages around the garbagrihas of Indian temples, such as the Kandariya Mahadeva or externalized as a ledge (jagati, platform) as at the Hoysala Chennakesava Temple at Somanathapura (1258.) The internal corridors, large image halls and spacious vestibules of Bagan’s temples were made possible by the use of “true” arches rather than corbelling, the only example found in South or Southeast Asia. This may, in part, account for why and how Bagan’s temples assumed such gargantuan proportions, e.g. the 6,500,000 brick Dhammayan-gyi (1170.)

At the Gawdawpalin Temple, six tiers (sometimes labeled “eaves,” like the kapota, the upper element of a Dravida shrine’s wall) rise like the tiers of the shikhara of a greatly enlarged Khmer prasat above the shrine’s 1st story with antefixes, aedicules of itself, at each of these “terrace’s” four corners. The first two tiers are highly compressed and inaccessible, covering the barrel vault of the inner corridor of the shrine’s 1st story but the 3rd suddenly emerges from the aedicules below, not as another squat “eave” but a 2nd story with its own porches and internal gallery around the primary image hall. Three more narrow terraces repeat the first two, providing the roof for the 2nd story. These tiers would complete a Khmer or Indian shikhara, except for an amalaka; instead, the Gawdawpalin’s vertical ascent continues with a distinctive “corncob” or “honeycomb” dome and spire, as if a Buddhist stupa’s anda (Sans.>“egg,” also resembling a “bell” with its finial as its “handle,) had been added to a six-tier shikhara, increasing this temple’s height to that of a twenty-story office building. By placing a tower on top of a tower (the six tiers of the two-story temple,) its builders unwittingly or uninhibitedly committed a solecism in the classical Indian architectural idiom. This second “corncob” tower’s shape still suggests a Hindu origin, perhaps unconscious, though likely not, since Bagan was in touch with the Buddhist university center at Nalanda in nearby Bihar. It resembles an Odisha rekka deul’s web of horizontal courses of gavakshas or horseshoe-arches broken by its pagas or latas, the vertical bands forming its rathas, e.g. the Rajarani Temple in Bhubaneswar, (see figure 9.) These giant finials, often toppled in Bagan’s earthquakes, had spires of their own, a hti in Burmese, composed of tiers of umbrellas, symbols of honor. These are said somewhat fancifully to be the origin of the tiers or hip roofs of a Chinese or Japanese pagoda above its shrine or reliquary chamber. A comparison with the “eaves” of the shikhara of the Gawdawpalin Temple, the aedicular tiers of the central tower at Angkor Wat or the 16-tala vimana or tower of the Brihadisvara Temple at Thanjavur (c.1010,) all suggest that the narrow aedicular stories, separated by a perfunctory kapota/kapotali or eaves of a Bagan gu, the tala of a Dravida vimana or the aedicular tiers of a Khmer prasat may have been at least a contributing architectural, if not theological, factor to the development of the pagoda. To sum up, at Angkor Wat, the central shrine and tower of the 3rd terrace can be read as an aedicule, antefix or crowning finial to the three enormous tiers or terraces beneath it; hence, the Khmer “temple mountain” is not a miniaturization of the shrine or prasat but its magnification, such that the shrine becomes an aedicule or part of itself and original and simulacrum change places.