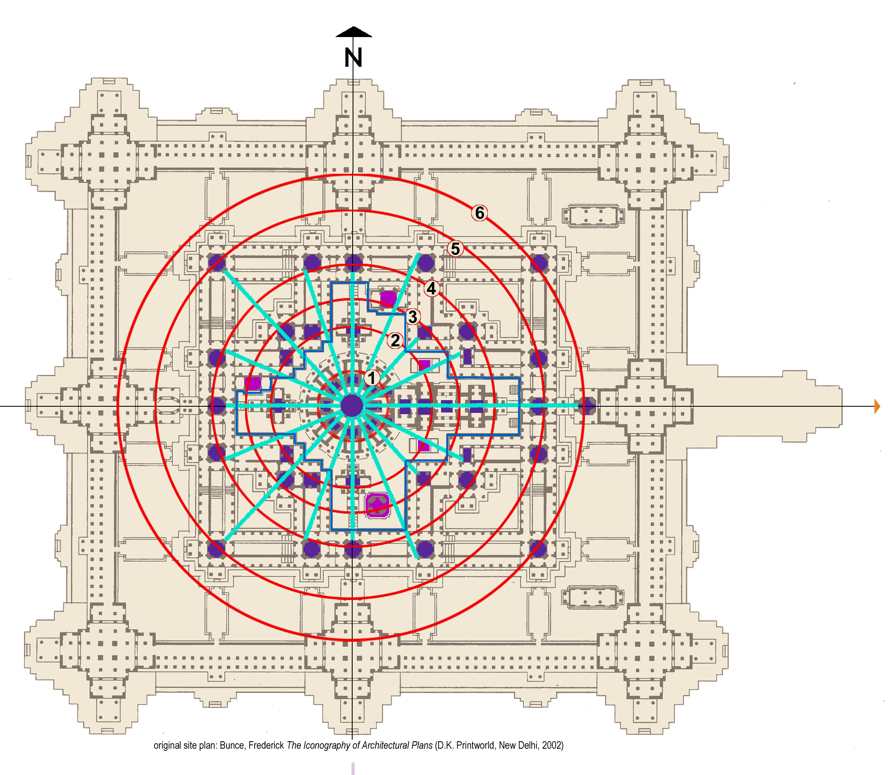

FIGURE 23C:

NON-ORTHOGONAL POSITIONING

OF THE FACE TOWERS

BAYON (1181-1220)

Face towers (52)

Rings of towers (6)

Radii bisecting the 8 rectangular shrines and

8 triangular niches of the central tower

Outline of the 3rd terrace

The Bayon is unique among Khmer monuments in taking the first steps beyond axial symmetry. It not only reconciles its symmetrical western and asymmetrical eastern sides in a mandala and places its central shrine at the center of a double panchayatana or quincunx of towers, as does Angkor Wat, it then begins to loosen this same symmetry by arraying its 52 cruciform face towers along radii and arcs ,perhaps, to syncretize the ideal form of Buddhism, a circle, with that of Hinduism, a square. The tentative (or simply haphazard) way it incorporates this opposing geometry into the Bayon’s plan suggests that its intent may have been to de-center or dis-place viewers rather than to impose a radial, but equally rigid, order around them. From this admittedly post-modern perspective, the purpose of the Bayon’s contradictions and anomalies may have been to resist any system rather than to substitute another occult one.

Orthogonal and radial geometries were juxtaposed at the Bayon as soon as the decision was made to convert the original cruciform shrine into a circular tholos with the awkward shapes that resulted. This also posed a more serious problem: how the conical tower with its sixteen radiating sections, as well as, the faces and aedicular shrines in the tiers above them, could be aligned across the cruciform 3rd terrace with its faces looking only in the cardinal directions?* Any sthapaka would know, as the number of projections of a square increases the more its outline resembles a diamond, a star and circle. At the Rajarani Temple (figure 9,) for example, as aedicular expansion increased the number of rathas, the square vimana began to approximate a turret or cone; inside it’s vimana’s massive walls, the garbagriha is decidedly stellate like its saptaratha cornice. The Bayon’s eccentric 3rd terrace also has elements which aedicularly expand the basic, square, Khmer prasat module, first into a fully-emerged triratha cross-on-square, (the underlying shape of the terrace, removing the two inserts,) whose corners are then redented to make it pancharatha on the west. If diagonals are drawn between the points where the redented square intersects the north, west and south arms of the superimposed cross, they form three sides of an equilateral octagon and three isosceles triangular sections when connected with the axial crossing. If these are then bisected, these lines will coincide with the walls of the western cardinal and northwest and southwest intercardinal shrines and two interstitial, triangular niches of the central tower. The parallel north and south sides of this notional octagon will be elongated because of inserts (12a and 12b,) but the facing, three, western sides would also be sides of an equilateral octagon. In Buddhist stupas, an octagon is the most common transitional form between a square or redented base and a round anda or “bell” and hti or finial, for example, the venerable Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon. As the following discussion will show, the shrines to the west of the north-south axis tend to fall on circles while those on the east disrupt both radial and orthogonal symmetry because of the characteristic Khmer off-set.

The two inserts (12a and b) responsible for the asymmetrical westward set-back result in corresponding towers on the east and west of the north-south axis falling on adjacent circles, tending to loosen the towers from their rigid right angle symmetry. The radial tropism traced in figure 23C and the diamonds' diagonals sketched in figure 23B, tend to draw the eye across and around rather than along the grid, while five “anomalous” towers make it unlikely that a viewer suddenly emerging onto the 3rd terrace would be able to fit the face towers into any coherent pattern. Instead, he or she might feel disoriented, lost without a fixed perspective and perhaps experience Glaize’s “spirit of confusion.” Nonetheless, these non-orthogonal geometries are not systematic or emphatic enough to suggest more than a destabilizing, centrifugal force pulling the face towers out of their concentric rectangles, hardly enough to introduce a counter-theme or alternative “Buddhist” geometry, more a dissonance undercutting the temple’s dominant orthogonal tonality.

At the Bayon, a radial geometry is already implicit in the eight shrines and their eight interstitial niches. If bisected, they project sixteen radii (turquoise lines, in figure 23C) at 22.5° intervals across the temple's rectangular 2nd and 3rd terraces which pass through or are tangent to all 52 face towers (except the four along the 2nd terrace's eastern edge and the "anomalous" tower in its northwest quadrant.) The face towers which fall on these radii arrange themselves in arcs which, in turn, could describe the circumferences of any number of possible circles spinning around the central shrine and its Buddha image. Six of these are traced in figure 23C:1) The first includes the central tower's eight cardinal and intercardinal shrines and the putative face towers above them on the circular, aedicular tiers which narrow like the rings of a stupa's anda and finial. 2) The second forms a ring of the ten face towers nearest to this central shikhara, (excluding the three protecting its eastern entrance,) consisting of: (a) the first four axially projected or medial towers; (b) on the west of the north-south axis, the first four towers laterally projected from those shrines and c) the first two, laterally projected from the eastern medial tower, namely, the flanking towers (mauve.) 3) A third circle is limned by: (a) the second two face towers, laterally projected from the medial towers on the west (the western corners of the red, inner rectangle of face towers in figure 23A;) 5) A fifth circuit grazes: (a) the three towers of the 1st east gopura; (b) the edges of the north, west and south inner porches of the 1st or outer gallery (like the outer diamond in figure 23B;) (c) and the second two, face towers laterally projected from the middle tower of the 1st west gopura (the western corner towers of the outer red rectangle of towers in figure 23A, as well as, of the 2nd gallery and terrace.) 6) Finally, a sixth circle is tangent to (a) the north, west and south inner edges of the largely destroyed 1st gallery; (b) the second two face towers laterally projected to the east from the middle towers of the 1st east gopura (the eastern corner towers of the outer, red rectangle of face towers in figure 23A, as well as of the 2nd gallery and terrace;) c) and the seventh, or easternmost, axially projected face tower over the vestibule to the 1st east triple gopura.

* One wonders if the Bayon’s builders realized they were faced with an instance of the age-old, insoluble, mathematical problem of "squaring the circle," i.e., how to fill an area which is a multiple of an irrational number,π r2 with a multiple of rational numbers or integers - without a remainder? As already noted, Indian sthapakas and, presumably, their Khmer counterparts, attached great importance to “remainders,” on the dubious assumption that the incalculable must ipso facto be of incalculable value. They seem to have been reaching for a solution when they increased the number of rathas and rotated them to form stepped diamond and stellate plans approximating a circle, for example, the 12-pointed star of the Hoysala Chennakeshava Temple at Somanathapura (1258,) illustrated on page 13. In the West, architects confronted the same problem when they needed to place a round dome over square piers in the so-called “zone of transition;” Brunelleschi’s revolutionary dome for Santa Maria dei Fiori (1436) is sprung from an octagonal drum. The architects of Hagia Sophia (536) were among the first to solve this problem by using four pendentives, triangular sections of a sphere with a diameter wider than the dome. At the Gumbad-i-Khaki in Esfahan’s Jami Mosque (1088) squinches or diagonal arches were sprung between the corners to make another octagon; the empty space behind them was eventually filled with tiers of smaller, coved squinches or muqarnas niches (cells, alveoli,) one of the most characteristic forms in Islamic architecture. At the Abdolsamad Tomb in Natanz (1309) a shallow cross-on-square is crowned by an octagonal roof filled with six muqarnas tiers converging in a 12-pointed star as at Somanathapura.

The question of the “zone of transition” could be seen as special cases of a deeper question facing any religious architecture: the transition from the two-dimensional plane of mundane existence to its vertical escape through the dome of the empyrean, the "heavenly spheres," and, finally, up the spire to the vanishing point of human perception and existence, the non-manifest absolute. This dynamic is embodied in the iconic shape of a Buddhist stupa, the convex curve of its bell which switches to the concave sweep of its finial where it vanishes in the lotus bud of satori and nirvana, the extinguishing of self. In the entirely different idiom of the Counter-Reformation Baroque, the lantern of Borromini’s hexagonal, stellate dome at Sant’ Ivo alla Sapienza (1660) ends in a flourish of volutes, then swirls around a temple with concave peristyle to spiral into a crown of flames, the self-immolating sapienza of the deity. Such sky-storming ambition has been attributed to the skyscraper – from the tower of Cologne Cathedral (1248,) to Wright’s unbuilt “Mile High Illinois” and the all-too-real London Shard (2009,) the Burj Khalifa in Dubai (2010) or, for that matter, every obelisk and pyramid of pharaonic Egypt. This vanity has invariably met with charges of blasphemy, “playing God,”’ like the asuras’ futile sallies on Mt. Meru or the biblical Tower of Babel, to say nothing of such humbling examples of architectural hubris, as the stump of Delhi’s Alai Minar (1311), the tipsy Asinelli (1109) and Garisenda Towers (1119) of Bologna, the collapsed first choir at Beauvais or the toppled htis (tips) which still follow every earthquake at Bagan. Nowhere has the seemingly insatiable curiosity for a view of the apophatic absolute been addressed as ingeniously as on the Bayon’s 3rd terrace, not by building a temple mountain to heaven but by turning the temple and everything around it into an illusion, thus affording a promised glimpse of the "world beyond thought."

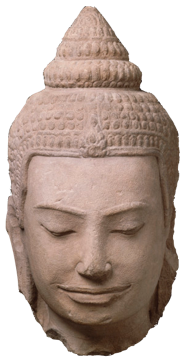

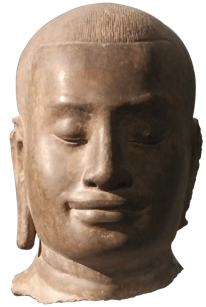

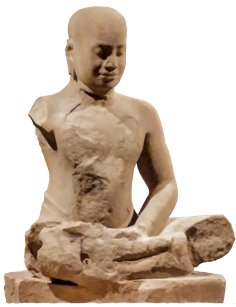

JAYAVARMAN VII (c. 1130-1220; r.1181-1220) IS THE ONLY KHMER MONARCH WHO LEFT PORTRAITS. READERS CAN DECIDE FOR THEMSELVES IF THE THREE BELOW RESEMBLE THE "FACE TOWER" UNDER THEM.

´

MUSEE GUIMET, PARIS

´

MUSEE GUIMET, PARIS

FOUND AT PRANG BRAHMADATTA, PHIMAI; COPY IN THE NATIONAL ANGKOR MUSEUM, SIEM REAP.

A “FACE TOWER” fFROM THE BAYON