Vertical Expansion:

The Dharmaraja Ratha

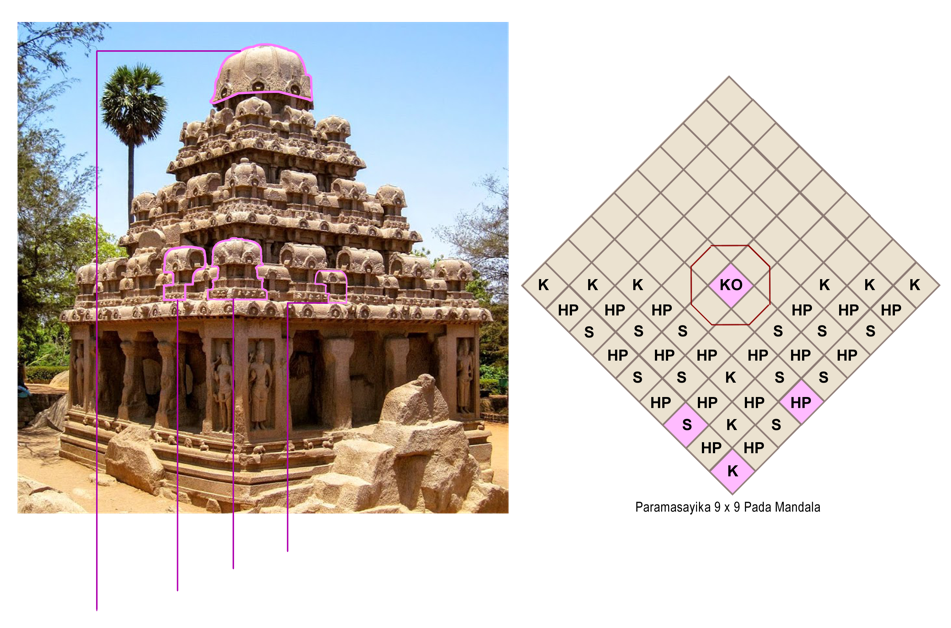

A prototype for “vertical expansion” can once again be found among the rock-cut monoliths of Mamallapuram, the vimana of the Dharmaraja Yudhishthira Ratha in figure 8. (Vimana is the Dravida or Southern Indian term for the Nagara or Northern Indian shikhara.). The ratha’s name commemorates the eldest of the Pandava brothers, heroes of the Mahabharata, whose surrogate father, Yama, was the Dharmaraja or judge of the dead. Ratha, in this case, signifies the vehicle or chariot of a god, cf. the Surya Temple at Konark and the Kailasa at Ellora. The shrine’s roof or tower, here a Dravida alpa vimana, is based on a 9 x 9-pada paramasayika mandala, arranged in a pyramid of 4 concentric squares, talas or tiers with 32, 24, 16 and 9 padas, each occupied by a single aedicule or shrine, except for the nine central Brahma padas, which hold a crowning, octagonal kuta aedicule. The matrix to the photograph’s right shows the repeated pattern in which the three types of aedicules, described beneath it, are strung; the aedicules circled in purple in the photograph have been shaded purple in the corresponding diamond.

FIGURE 8: ANALYSIS OF AEDICULES OF THE DHARMARAJA YUDHISHTHIRA RATHA, MAMALLAPURAM (c.650)

S = shala aedicule

K = kuta aedicule

HP = harantara-panjara aedicule

K-O = octagonal kuta aedicule

K =

S=

a square kuta aedicule or “cap,” a single cella shrine, like the nearby Draupadi Ratha in figure 3, except sometimes open-sided and surrounded by a vedi/vedika, fence, railing, altar; it rises above a vyalamala (Nagara prati) representing the joists or rafters of its putative 1st story (cf., the non-structural triglyphs of a Doric frieze or the dentils of an Ionic architrave.)

a rectangular, barrel-vaulted shala aedicule with ogival or “horseshoe-shaped,” open gables at either end, patterned after the gavaksha windows at the opening of rock-cut Buddhist chaitya/ caitya halls, themselves imitations of earlier, rectangular or apsidalshrines made with bent bamboo, rush or palm frond roofs.

HP=

K-O=

a harantara-panjara aedicule, a panjara aedicule (i.e., a shala aedicule seen end-on,) which projects as a dormer or window, (the ubiquitous gavaksha or kudu,) into the harantara, the barrel-vauled cloister or gallery linking the hara or "necklace" of shrine aedicules around the prastara or parapet of a tala of a Dravida temple. Although, as here, it appears to rise on a stambha or column from the cloister's vedi or railing, since the vedi is only a molding and the pillar only a pilaster, the aedicule ia referred to as arpita or “applied.”

the octagonal kuta aedicule occupying the nine central or Brahma padas which crowns the vimana of this Dravida shrine.

Two-Story Aedicules: The 1st tala with its hara of kuta, shala and harantara-panjara aedicules rests on the eave (kapota) of the ratha’s full-height ground floor. Prof. Hardy stresses that aedicules have two-stories, a ground floor, solid-walled, pillared or pilastered, with a shrine and roof above it. The compressed “intermediate floors” of the upper two talas can be glimpsed, in the photograph above, in the shadows behind the roofs of the aedicules of the lower two talas, visible only as pilasters and over-size potikas (brackets.) These support the kapotas or eaves of these stories on top of which rest the hara of shrines of each tala.

This introduction departs from this usage in sometimes referring to a discrete, “standard” Khmer shrine or prasat as an “aedicule,” including both the ground floor shrine and the four, “aedicular” layers constituting its tower (prang, vimana, shikhara,) in this case, one aedicule per tala or tier. These might more accurately be described as compressed replicas emerging from a shrine in a vertical version of what Hardy refers to as “staggering” or “telescoping.” The Khmer used this same type of shrine with remarkably little variation over five centuries where it appears as an aedicule, in the traditional sense, only as antefixes on the corners of the emergent aedicules or talas of its tower.They built their temples, not by accreting such miniature aedicules, but by projecting at a distance, near duplicates of their prasats as corner shrines, gopuras or quincunxes of towers, accounting for the greater horizontal extension of Khmer temples compared with their compact Indian counterparts.

Whenever possible on this website, the notation for aedicules and their placement on a temple has been adapted from the system developed in Prof. Adam Hardy’s pioneering Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation: The Karnata Dravida Tradition (Abhinav Publications, New Delhi, 1995.) They have been supplemented and modified to conform more closely with Khmer practice.

9 x 9-pada paramasayika mandala

In Dravida shrines, like the Dharmaraja Ratha, all the aedicules are fully emerged but they are not all aedicules of the core, a square kuta alpa vimana. Its square ground floor and three square talas, (Hardy does not count the kuta dome and griva “neck” recess beneath it as a tala,) without their haras of shrine aedicules would be equivalents of the shrine and four aedicular stories of a Khmer prasat module. In the latter case, the vertically projected stories are true aedicules, miniaturized versions of the underlying shrine, in keeping with the Khmer aversion to variation, as opposed to the aedicular innovation of their Indian counterparts. The following section will discuss how Nagara or Northern Indian temples achieved vertical expansion simply by extending the rathas or pagas of their core shrines or cellas in continuous strips converging at the top of their shikharas beneath their amalakas. Smaller versions of this convex tower or urushringas emerged partially or wholly from this core, like foothills around Mt. Meru, themselves two-story aedicules of the core shrine.

“Aedicular expansion” opened the possibility for the limitless proliferation of shrines and deities to populate them, an opportunity not lost on later Indian temple architects and their patrons. This could sometimes be carried to extremes, for example, in the temple cities of Tamil Nadu, where the Ranganathaswamy Temple at Tiruchirappalli–dedicated to Vishnu–sports India’s largest tower. There thirteen tiers or talas of brightly painted aedicules overflow with celestial beings, theirs heads poking over every vedi railing and through each gavaksha dormer.

SRI RAGANATHASWAMY TEMPLE, SRIRANGAM, TIRUCHIRAPALLI, TAMIL NADU (16th, 17th CENTURIES)