PHNOM

BAKHENG

(907)

PHNOM

BAKHENG

(907)

EAST FACE, PHNOM BAKHENG (907)

EASTERN STEPS, PHNOM BAKHENG (907)

ANASTYLOSIS, PHNOM BAKHENG (2004-2019)

ANASTYLOSIS, PHNOM BAKHENG (2004-2019)

RESTORATION, PHNOM BAKHENG (2004-2019)

Yashovarman I (r.889-915) built his own state temple, Phnom Bakheng, on a small hill between the sites of the future Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom,15km northwest of his father's temple mountain, the Bakong. Thus, Phnom Bakheng (phnom means hill in Khmer) was not just a “temple mountain” but a "mountain temple" as well, the second temple mountain of the Angkorian era. At roughly the same time, Yashovarman I built two smaller mountain temples, Phnom Bok to the northeast and Phnom Krom to the south, on the only other promontories overlooking the surrounding plain, (described in the following two sections of this anthology.)

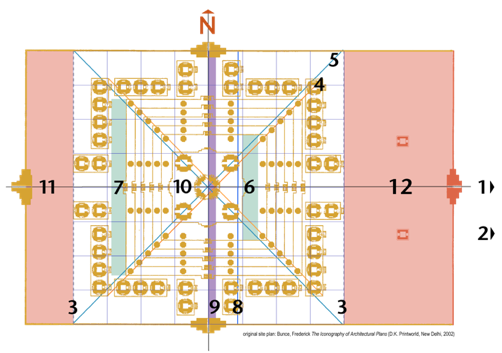

The photograph above was taken from the point where the flight of steps and "elephant path" (1 and 2, on the site plan, figure 13 at right) which rise from the highway at the hill's base in what constitutes the temple's 2nd or outer enclosure, before reaching the crest of the leveled surface of the 1st enclosure (12) and the pyramid's five terraces, which were carved from the summit of the hill. Rather than make the pyramid a direct extension of the hill, it has been set back (12) from the 1st enclosure's edge to emphasize it as a discrete, second hill or temple mountain. At the same time, it replicates the first, since its incline, significantly steeper than the Bakong's, continues that of the hill. Thus, Phnom Bakheng could be seen as a smaller version, "aedicule" or shikhara of the small natural mountain on which it sits, just as its towers’ five shikharas could be seen as aedicules of the stepped pyramid itself and the hill of which it forms the summit; all are symbols of the "Platonic form" of mountains, Mt. Meru which they imitate. The 60 small shrine aedicules that line its terraces and 44 larger ones that guard its base must be added to this process of miniaturization and multiplication.

The photograph at right, taken from the foot of the eastern staircase looking up at the five tiers of small shrines, shows the 45° incline of the pyramid's terraces which would make it impossible to see any of its panchayatana of five shrines. Here, the additional westward setback (6,) the green strip on the site plan figure 15, of the towers and plinth on the pyramid would delay the point when climbing this staircase at which the top of the central tower, regardless of its original height, would come into view. Later Khmer temple mountains would have even steeper slopes, as much as 70%, but in these cases, such as Ta Keo, the tower's pedestals reach almost to the edge of the upper terrace.

Phnom Bakheng underwent a meticulous five-year restoration under the direction of APSARA (Authority for the Protection of the Site and Management of the Region of Angkor,) the branch of the Cambodian government in charge of the Angkor Archaeological Park with a staff of over 500. It has spear-headed efforts to stop the looting and international antiquities trafficking which plagued Angkor during the Khmer Rouge period and its aftermath, described in greater detail with reference to Koh Ker, a later temple. The restoration of Phnom Bakheng was supported by a grant from the United States Department of State made during the Obama Administration. The United States thus joined an international consortium including Austria, China, France, Germany, Japan, the Nordic countries and even North Korea, which have provided the majority of the funds to make Angkor not only one of the largest archaeology projects ever undertaken but also one where the most scholarly and scrupulous restoration practices have been consistently implemented. This is in marked contrast with the ersatz towers, based on scant evidence, which have defaced the equally remarkable monuments at Bagan, sponsored by Myanmar's unpopular, military regime to impress its citizens and tourists with thousand-year-old monuments which look "as good as new" -because, in many instances, they are. This “vandalism by restoration” prompted UNESCO to condemn these efforts as turning Bagan into an "archaeological Disneyland." APSARA has protected Angkor from its more than 6 million annual visitors by providing a well-developed tourist infrastructure which offers convenient access to the archaeological park but only through carefully restricted, diligently enforced routes.

The current "best practice" in archaeological reconstruction is called anastylosis (Gr.> ana- again + stylou to erect). It was first developed by the Dutch in their Indonesian colonies for the restoration of temples such as Prambanan and Borobudur, which coincidentally may be the closest antecedents to Khmer temple architecture. This painstaking, conservative method was adopted by the École Francaise d'Extreme Orient (EFEO) in its work throughout Cambodia and has been continued since independence in 1953. It consists of reconstructing monuments only from materials found at a site (or which can be proved to have once been a part of it through radiocarbon dating and geological analysis). No shard or block is replaced unless its original position can be established with reasonable certainty. Parts of the building which are structurally unsound are disassembled and all these pieces numbered and keyed to a stone-by-stone blueprint of the likely original monument. These unstable areas can be extensive because of Khmer building practices and the avid growth of tropical vegetation, which invades any spaces that may develop with the passage of time. New materials needed to ensure the structural integrity of the monuments or make possible the return of collapsed parts to their original positions are not disguised or "distressed" (artificially aged) but clearly marked as modern interpolations. Thus, the visitor will occasionally encounter newer bricks stamped with "CA" designating them as restored by "Conservancy Angkor."

The photo at right slide shows some of the numbered blocks around the base of Phnom Bakheng waiting to be repositioned on the temple by the trained artisans in the slide below. 300,000 such blocks were similarly waiting to be reassembled at a later temple, the Baphuon (1061,) when the Khmer Rouge took control of Cambodia in 1975. In the subsequent chaos and genocide, the key for repositioning the stones was lost or destroyed, leaving what has been described as "the largest jig-saw puzzle in the world." It took the joint effort of the French and Cambodians until 2011 to put the Baphuon back together again, 51 years after the EFEO began the task.

The APSARA authority has trained local Cambodian craftsmen and women in the techniques and science of restoring their own monuments. The working conditions, it is hoped, will set a standard for construction practices throughout Cambodia which are often harrowing. These workers have been provided steel-reinforced, plank scaffolding (not knotted bamboo lattices), safety helmets and protective masks whose use is mandatory. They are worn even though sandblasting equipment and electric lathes are, in general, not used, only modern equivalents of the original tools like steel alloy chisels, which nonetheless can produce harmful particulates. The unusually seamless fit of Khmer ashlars is being recreated using the same method, sprinkling an abrasive powder between adjacent stones, then rubbing them against each other until their faces are smooth. The original vegetable mortar which decays and feeds invasive strangler figs and cottonwood trees has, however, been replaced by inorganic sealants.

RESTORING ANGKOR – ANASTYLOSIS

43