PHIMAI (c. 1100)

NAGA BRIDGE AND TERRACE TO THE 2ND SOUTH GOPURA, PHIMAI (c.1100)

PHIMAI (c. 1100)

NAGA BRIDGE AND TERRACE TO THE 2ND SOUTH GOPURA, PHIMAI (c.1100)

Phimai marks two important developments in Khmer temple architecture: 1) It is widely regarded as the prototype for both the characteristic ogival profile of the towers and the style of bas relief carving of Angkor Wat, begun perhaps a decade after it; 2) it is the most fully realized example of the "linear expansion" of a Khmer shrine or prasat, the model for most temples built over the next fifty years, including Phnom Rung, Thommanon, Banteay Samre, Wat Athvea and Chau Say Tevoda, while it influenced the monastic foundations of Jayavarman VII (1181-1220.) "Linear expansion" is the subject of section III of the introduction which uses Phimai and the Kandariya Mahadeva temple at Khajuraho as examples.

This photographic survey of Phimai, like that of Preah Vihear, will follow the temple's liturgical axis as the original worshippers and today's visitors encounter it. At Phimai, that axis is unconventionally oriented not from east to west or from north to south (as at that earlier mountain temple), but from south to north, though still aligned with the Khmer capital 375 km to its south like a line of force issuing from it. This temple marks the northern limit of the Khmer Empire in its day and terminus of the Royal Road from Angkor passing through Banteay Chhmar and Phnom Rung. (Coincidentally, Phimai today is where the freeway ends from Bangkok through Nakhon Ratchasima or Khorat 62km to the southwest in the Isan region of Northeastern Thailand.)

The temple likely dates from the reign of Jayavarman VI (1080-1107,) a prince of the powerful northern Mahidharapura family, who overthrew Harshavarman III (1066-1080,) the brother of Udayadityvarman II (c.1050-1066,) the builder of the Baphuon, and, in so doing, launched a new northern dynasty. Jayavarman VI may, in fact, not have ruled from Angkor but from his ancestral estates which might explain the construction of such ambitious temple complexes as Phimai and Phnom Rung, far removed from Angkor, the traditional center of power where there was a notable paucity of new construction during his reign.

The area around Phimai had a history of Mahayana Buddhism stretching back to the Dvaravati and Mon kingdoms of the 6th through 8th Centuries, before the re-founding of the Hindu Khmer Empire by Jayavarman II, his assumption of the title of chakravartin or "world leader” and his installation of the Saivite devaraja cult on Mt. Kulen in 802. This legacy presumably accounts for the dedication of this temple, typically Khmer and Hindu in other respects, to the Vajrayana/Tantric bodhisattva, Trailokyavijava, "Lord of Three Worlds." This name appropriates a familiar epithet for Shiva, derived from his linga which swelled from the ocean depths to heaven, overwhelming Vishnu and Brahma. It also alludes to a similar honorific for Vishnu, Trivikrama, from a competing myth, in which the god's fifth avatar, the dwarf Vimana, strode across the earth, air and underground in "three steps." In addition, this bodhisattva delayed his entry into parinirvana or non-existence specifically to convert the Vedic gods to Buddhism. The contradiction of the rulers of an ostensibly Hindu empire, legitimized by their initiation into the Saivite devaraja cult, constructing such a temple evidences the Khmers' relaxed or simply cynical attitude towards doctrinal distinctions. This appears to have been a constant through all their dynastic changes, with the notable exception of Jayavarman VIII's (1249-1295) futile, last-ditch stand against the growing popularity of Buddhism. When that religion triumphed in Cambodia, however, it was the Theravada, not Mahayana or Vajrayana.

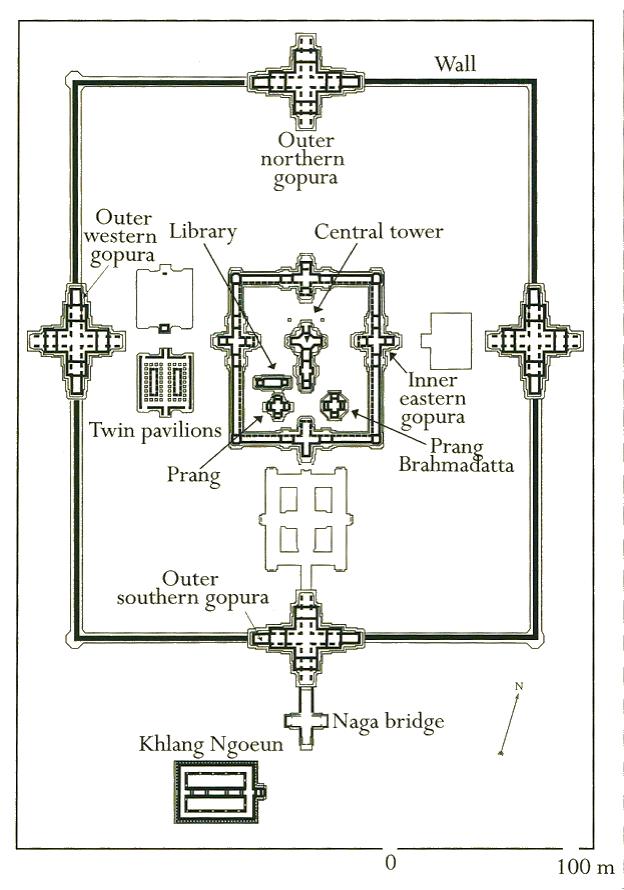

Phimai has been faithfully restored by the Thai Department of Fine Arts and sits at the center of an impeccably maintained historical park. It demonstrates a too-rare respect for the monuments of an different ethnic group and religion. On this plan, the 1st enclosure and its gopuras are referred to as "inner" and the 2nd's as "outer;" it should be labeled "middle;" since the temple had a large 3rd enclosure indicated only by a black border here. It contained the Khlang Ngoeum, thought to be a "palace" or hostel for visiting dignitaries and pilgrims to this remote site, as well as the naga bridge and terrace pictured above. This third enclosure was surrounded by a moat and walls, still visible, and is occupied by the bustling market town of modern Phimai. At the beginning of the 12th Century, it would have contained the lay, support staff for this ambitious temple complex. Today it offers an impression, on a much smaller scale, of what Angkor Wat's outer enclosure, also surrounded by a moat and home to upwards of 200,000 people, might have originally looked like. This site plan also reveals the scattering of ancillary buildings whose consolidation into one coherent network of galleries and terraces was a principal achievement of Angkor Wat.

SITE PLAN, PHIMAI (C.1100)

1ST SOUTH GOPURA AND GALLERY, PHIMAI (C.1100)

Looking north from beyond the naga bridge and 2nd south gopura, the expanse of the 1st enclosure’s south wall and 1st south gopura fill the view. In the foreground, a "cruciform terrace" is formed by four, now-empty, stone-lined pools which some scholars identify as representing the "four sacred rivers" of India. [The number of these rivers is in dispute; included on most lists are the Ganga (Ganges,) its tributary, the Yamuna, which runs past Delhi, the Sarasvati, an underground river of uncertain location, possibly because legendary, and the Narmada, flowing through Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. In addition, the Godavari and Krisha in Andhra Pradesh, the Kavari in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu and the Sindhu (Indus,) now in Pakistan, are all contenders.]The structure may have been a prototype for the raised stone "cruciform cloister" linking the 1st and 2nd galleries and terraces at Angkor Wat and might confirm that it too was filled with water, similar to the inner enclosure at Banteay Samre. Four similar ponds precede the 1st enclosure of the nearly contemporaneous temple at Phnom Rung, also in Thailand. The long south gallery of the 1st enclosure contrasts red brick and laterite walls with white sandstone trim around the doors and windows. Similarly, inside that enclosure, two red ancillary shrines to the southeast and southwest frame the white sandstone central temple and its prang or shikhara. Polychrome stonework does not appear again until the very different use of green, pink and gray sandstone at Preah Khan (1191) and Banteay Kdei (c.1200.)

After passing through the cruciform 1st south gopura, which penetrates deeply into the 1st enclosure, the ardhamandapa or south entrance porch to the temple is just a few steps away, in contrast with the wide 2nd enclosure. Its pediment shows Shiva Nataraja, "Lord of the Dance" and "Destroyer of Worlds" at the end of each mahayuga. He is placed within the parenthesis of a similarly ferocious Tantric Buddhist deity, Hejavira, on the pilasters, who here ooks more cherubic that fierce. In the photo, the two pediments above the ardhamandapa, through a visual illusion, appear to continue a cascade of toranas (nasi) or horseshoe arches down the shikhara's four aedicular tiers, the sukanasa and the staggered shala roof of the mandapa, to the south porch, similar to a bhadra, late or raha paga, the central vertical projection of a Nagara (Northern Indian) temple.

SOUTH PORCH (ARDHAMANDAPA,) PHIMAI (c. 1100)

PRANG BRAHMATHAT, PHIMAI (c.1100)

This laterite shrine, in contrast with the main, white sandstone temple, has four talas or aedicular tiers and the usual four porches and portals of a pancharatha Khmer prasat. It is squeezed between the southeast corner of the mandapa, in the background at right, and the southern wall of the 1st enclosure. It was here that a seated statues of the Buddhist king, Jayavarman VII (1181-1220,) and his wife, Jayarajathevi, were found.

WEST FACE, MANDAPA, PHIMAI (c.1100)

The conjoint “southern porch” or extension of the cella and the antarala linking it with the mandapa can be distinguished by their one blind and one baluster windows; above them rises the sukanasa's pediment, level with those of the north, west and east porches. The lower barrel-vaulted roof of the antarala is level with that of the ardhamandapa while the mandapa has a higher ”false," half or aedicular story with a lower, second eave, a chadya, canopy, or awning over its aisles.The mandapa’s cross-section, a two-part barrel-vaulted arch is the characteristic profile of a Dravida valabhi shrines, sometimes called a tri-lobed or split gavaksha ("cow's eye") or torana. The three roofs also could be read as a double, staggered shala shrine, the two lower telescoped roofs constituting one stagger and the pediment and dormer over the mandapa's door acting as a panjara aedicule or nasi projection In the foreground, the red sandstone Prang Hin Daeng is thought to have been a brahmanic sanctuary, possibly predating the other shrines.

The lintel (in shadow) above the western portal shows an incident from the Ramayana where Rama and his brother, Lakshmana, are ensnared in the magic nagapasha or net of snakes by Indrajit, son of the demon king of Lanka, Ravana, who has abducted Rama's wife, Sita. In the register below, their monkey allies comfort the two heroes. From the double pediments above, Garuda, Vishnu's mount, (of whom Rama is sometime considered an avatar, as Lakshmana of the naga, Shesha or Ananta,) descends at Hanuman, the monkey general's, urging to free the brothers.

TRAILOKYAVIJAYA, LINTEL BEFORE THE CELLA, PHIMAI (c.1100)

This lintel between the mandapa and the antarala or vestibule to the garbagriha shows the bodhisattva, Trailokyavijaya, literally "Victor of the Three Worlds," dancing, like his disciples in the lower register. The bodhisattva is identifiable by his eight arms and four heads (the fourth is at his back.) Since the role of this particular bodhisattva to whom Phimai is dedicated was to convert the Vedic gods, his dance of victory here is meant to show the superiority of Buddhism over Shiva Nataraja's Hindu tandava or "dance of destruction" depicted on the lintels over the temple's southern portal and its 1st south gopura – both passed through on the way to this central shrine. While Brahma, alone among the Trimurti, recognized the superiority of Buddha's dharma over polytheistic maya or illusion, Shiva refused to convert to Buddhism and is often portrayed, along with his consort, Parvati, being trampled by the 22-armed Prajnaparamita, goddess of knowledge, sometimes carrying a kapala, a skull cup for blood, with her tongue in the shape of a driguk or flaying knife, attributes adopted directly from Shiva's own terrifying female aspects, Bhairavi and Kali. Lest the comparison be missed, on this lintel the three-headed, six-legged "Victor of Three Worlds," Trailokyavijaya, seems to be doing his own "dance of destruction" on the bodies of Shiva and Parvati, stretched across their elephant-headed son, Ganesha. Parallels with Aztec human sacrifice are tempting - especially since there are reports of human sacrifice at mountain shrines in Cambodia as late as the 19th Century, discounted since the victims were "only criminals already condemned to death." This symbolism may represent an atavistic memory of a time in the history of most Neolithic people abefore animal sacrifice was substituted for human, an account mythologized in the story of Abraham and Isaac.

BUDDHA UNDER MUKHALINDA, PHIMAI (c.1100)

A statue of Buddha was placed where the temple's north-south ritual axis intersects its widest point, the transept or east-west axis. Buddha, during the sixth week after his enlightenment at Bodhi Gaya, while meditating under the bodhi tree, was protected from a torrential storm by Mukhalinda, the seven-headed, king of the nagas. It was at this time that Buddha said, "Happy is he who no longer says I am." This is one of the most frequent forms in which Buddha was portrayed at Angkor, including the smashed cult statue found at the bottom of a cistern at the Bayon.

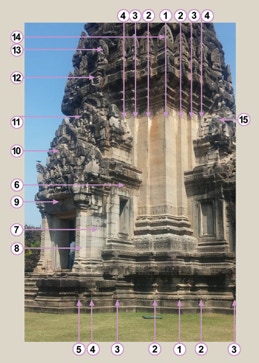

FIGURE 4: ANALYSIS, NORTH PORCH,

PHIMAI (c.1100)

NORTH PORCH AND SHIKHARA, PHIMAI (c.1100)

A series of pediments with double, split arches or cusped toranas unify the inner and outer, partially-emerged north porches with the four tiers of the shikhara above them, similar to the apparent cascade or bhadra on the temple's south face. Starting from the base, the lintel between the pilasters, over the colonettes and outer porch shows another scene from the ever-popular Ramayana, Hanuman and his monkey army constructing a bridge to Lanka (Sri Lanka) where Sita, Rama's wife, is held captive by the demon, Ravana. The lowest pediment above the lintel shows devatas paying tribute to Shiva on Mt. Kailasa. The second spanning the partially-emerged inner, northern porch is simply a backing with torana and garland; its tympanum is covered and uncarved. A third pediment rises behind it over the inner porch's gable roof, atop which Garuda, Vishnu's mount, appears to hold up the entire shikhara, representing Mt. Meru, lifting it or flying with it from earth to the empyrean, (as he does the 3rd enclosure walls at Preah Khan.) The center antefix of the first or lowest aedicular tier is a hood-like niche with Varuna, god of the winds, on four hamsa or geese, rather than his usual vehicle, the makara; niches over the adjacent rathas contain directional guardian kings, while those at the corner, karna or kanika rathas, at the upturned ends of the pediments' garlands, continue the motif of rearing seven-headed nagas, introduced with the Buddha statue in the shrine. These create the characteristic continuous convex or ogive curve of the shikhara which replaced the stepped pyramid to become the distinctive profile of the towers of Angkor Wat and its style. The pediment over the "portal" of the 2nd aedicular tier is missing; its god appears to have been driving another team of mounts - perhaps Brahma's geese, Surya's horses or Saraswati's swans. The avian theme continues on the third pediment with Skanda, god of war and son of Shiva, mounted on his mount, the peacock; the fourth and last pediment has chipped away. Each of these four "talas" is an increasing compressed aedicule of the shrine below, repeating its rathas though little more.

2ND NORTH GOPURA FROM THE SOUTH, PHIMAI (c.1100)

The cruciform, 2nd north gopura, seen above looking north from inside the 2nd enclosure, like its counterpart on the south, is unusually broad and deep suggesting a gallery or colonnade across its long northern and southern arms, as well as east-west gallery. The modern town in the 3rd enclosure is visible just beyond. This reverse view (at right,) from the northern portal of the 2nd north gopura looks south down its axial arms to the 1st north gopura and through it to the north porch and shikhara of the prasat,

2ND NORTH GOPURA LOOKING SOUTH,

PHIMAI (c.1100)

60