ANGKOR WAT (1113 – 1150)

ANGKOR WAT (1113 – 1150)

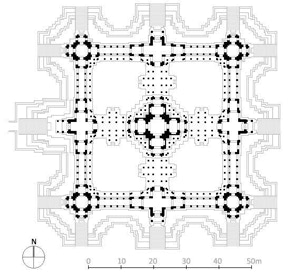

Angkor Wat's iconic profile has become such a cliché that it makes it difficult to perceive the intricate design binding its three terraces and nine towers into a powerfully integrated whole. The view in the photograph above is the one image most of Angkor's more than six million annual tourists will remember, a silhouette printed indelibly on the mind of anyone who has seen it. Emblazoned on the Cambodian flag, it is a unifying symbol for a traumatized nation. The temple is both the largest religious structure and stone building in the world; no one has ever been tempted to equal it. It beggars, indeed exhausts, the imagination, so overwhelmingly vast, it is difficult to see beyond its immensity. (Figures 12 and 13 of section XII of the introduction, “Synthesis: Angkor Wat” analyze how three inter-locked structures –– a cruciform cloister, crosswalk and colonnade –– bind virtually every part of the monument together.) As with previous temples, the photographs in this brief survey have been loosely arranged to follow the route followed by most visitors to the temple with occasional detours to features necessarily neglected in the introduction’s discussion.

MOAT AND WEST FRONT, 4TH ENCLOSURE, ANGKOR WAT (1113 -1150)

This colonnaded gallery parallels the moat around the 203 acre, 4th or outer enclosure of Angkor Wat, "the city in the shape of a temple." It is not a defensive perimeter but a loggia, showing the confidence of the Khmer Empire at its height, acting as a frame and foil for the “temple mountain” which waits behind it. This gallery does not contain the temple's celebrated mural bas relief but it is carved with the same precision and seemingly inexhaustible invention as the rest of the temple's acres of walls, including by one count its 2,796 apsaras - each different. Behind this gopura a spacious mall, crossed by an elevated causeway, passes two substantial "libraries" and two reflecting pools on its way to the cruciform terrace before the open colonnade of the 3rd enclosure or 1st terrace and gallery containing its more than 800m of narrative bas relief.

THE BAS RELIEF

MOLD OF LINTEL, 4TH WEST GOPURA, ANGKOR WAT (1113 -1150)

This mold of a lintel from the 4th west gopura illustrates the mature Angkor Wat style of sculptural decoration; a deeply incised garland whose undulations have been regularized into three rectilinear indentations with tightly curled swags between them, ending in inward-swirling volutes. Within its dense foliage, apsaras sing, devatas dance, warriors posture and rishi meditate; no space is left unchiseled, as if its carvers had a horror vacui. The apotropaic kalas or kirtimukhas of lintels past have been banished; no makaras or nagas snarl from the garland's ends; in a more self-assured age, there are only gods, their human counterparts and an auspicious future (which would soon prove illusory.) At the lintel's center, Vishnu sleeps on the Ocean of Milk aboard Ananta/ Shesha (Sans. > ananta, "endless" + shesha, "the remainder,”) after the destruction of a degenerate universe in Hinduism's cyclical “creation myth." A lotus sprouts from the god’s navel on which four-headed Brahma prepares to create a new Golden Age or krita yuga, the reign of Suryavarman II. *

This brief overview will not presume to describe the 800 meters of narrative bas relief around the 1st gallery (8, in the site plan below,) already described in detail in the guidebooks recommended in the introduction. Unlike Ta Keo or Banteay Samre, the 1st gallery of Angkor Wat is an outward-facing vaulted colonnade; since its murals overwhelmingly mirror life in a feudal society, not unlike that around the temple, as reflected in the immensely popular Hindu epics and myths, and therefore comprehensible to all. Simultaneously, these walls acted as a barrier between the profane, samsaric world governed by karma pictured on them and the sacred, often occult rites within, leading from the terrestrial plane to the divine symbolized by its upper terraces, a simulacrum of Mt. Meru. Each of the eight individual murals seem meant to be viewed like a long narrow strip of film, where the viewers, not a projector, advance the seamless frames. Unlike the episodic panels at the Baphuon, Angkor Wat presents history as a continuum, one is tempted to say, cycle.

Therefore, it is all the more confounding that the temple's numberless exegetes have been unable to propose a satisfactory narrative or argument explaining their sequence around the 1st gallery or, indeed, any underlying thematic unity. There is not even agreement whether they should be viewed with the murals on one's right in keeping with conventional solar or clockwise pradakshina, ritual circumambulation, or on one's left in a counter-clockwise prasavya direction, associated with death but consonant with the temple's west-facing orientation and hypothetical posthumous function. Since there is no evidence of ritual circumambulation at Angkor, this question may be moot. Others have suggested that the murals are arranged analogically across the gallery rather than sequentially around it, as scenes from the Old and New Testaments are sometimes paired. In the absence of any discernible didactic purpose, such as found at Borobudur in Java, and, given that each mural seems complete in itself, they may be simply a gallery of myths Suryavarman II saw as emblematic of his reign.

*The fact that this is a molding testifies to the EFEO's (Ecole Francaise de lExtreme Orient) commitment to preserving most of Cambodia's patrimony in situ rather than shipping it back to Europe on the spurious grounds that only there could it be safely preserved. One need only compare Lord Elgin absconding with the Parthenon "marbles" or Napoleon plundering Egyptian obelisks and Italian paintings less than a century before to appreciate the EFEO's comparative restraint. For their part, Cambodians had used Angkor's monuments as quarries for later Buddhist temples, while their self-proclaimed liberators, the Khmer Rouge, flogged these vestiges of a past they despised to "antiquities dealers" and their museum enablers who sometimes placed orders for the choicest, published pieces.

COLONNADE, WEST FACE, 1ST GALLERY

ANGKOR WAT (1113 - 1115)

"THE BATTLE BETWEEN THE DEVAS AND ASURAS," WESTERN MURAL, NORTH GALLERY,

1ST TERRACE, ANGKOR WAT (1113 -1150)

Most tourists visit the 1st gallery (8) in a counterclockwise direction because the best-known murals and myths are concentrated on the south side of the temple – "The Battle of Kurukshetra," "The Procession of Suryavarman I's Army," "The Heavens and Hells" and "The Churning of the Ocean of Milk." These are followed by some crudely carved, formulaic murals thought to date from the 16th Century which discourage many from persisting to the two galleries bordering the northwest corner. The 12th Century sculptors appear to have worked from the western entrance towards both the north and south, so these are among the most dynamic and vigorously carved murals of the entire 1st gallery. The one on the northern west face, the "Battle of Lanka," the climax of the Ramayana, is a clear pendant to the "Battle of Kurukshetra," the climax of the Mahabharata, to its immediate south across the 3rd west gopura. This photo shows a detail from the western mural on the temple’s north face, "The Battle Between the Devas and Asuras" for control of the "Three Worlds," the equivalent in Hindu mythology of the Gigantomachy in Greek or Satan’s assault on Paradise in Milton's Paradise Lost. It depicts the brutality of battle candidly but without judgment as unavoidable – similar to the Iliad, the epic of another warrior society sharing a feudal, militaristic ethic. The mural depicts with unsparing frankness but respect the terrible intimacy of hand-to-hand combat joining opponents in a moment when the only certainty is that one must kill the other.

The scenes in this panorama do not unfold as a sequence of incidents in a narrative; indeed, they often make it difficult to distinguish one side from the other or to know who has the advantage. Thus, they become particular instances of an ineluctable general condition, perhaps war's generalization and leveling of individuals, motives, causes, victory or defeat, to an impersonal, self-propelled killing machine. If so, that would suggest sentiments at variance with the overt values of the sculptors - and their society and may be just a modern projection. The details above vividly evoke the chaos of battle without becoming chaotic itself, thereby avoiding "the fallacy of imitative form." The tangle of arms and legs animating the surface is, on closer inspection, deftly choreographed, the seemingly dismembered limbs draw the eye across this 92m epic, stone canvas. The two antagonists in high relief are, in fact, mirror images of each other, their flexed legs and raised swords at similar angles, their horses' heads overlapping as one, their round shields at the center, reflecting the devas and asuras as mere inverses of each other. Such symmetries demonstrate Khmer sculptors' ability to create rhymes and rhythms which give coherence to the welter of particulars and flurry of events which could never read as a coherent linear sequence. For example, the legs and arms of the large, striding figure at the upper center begin a rotary motion of right angles continued by the bent legs to their right and the warrior charging in the opposite direction to the left, which culminate in the torqued stances, already noted, of the mirrored warriors in the foreground. In this way, individual figures become cogs in a spinning wheel, the relentlessly rotating chakra of divine law and karma, or, perhaps, the goose-step of a swastika's crooked cross.

In contrast with the narrative historical and mythological murals surrounding the 1st gallery, the 2nd gallery (6) and terrace (5) are usually characterized as austere and penitential. Their sole decoration consists of 1024 bas relief of apsaras or "celestial nymphs. (It is probably not fortuitous that this recent census equals 210, though whether this should be attributed to numerology on the part of Angkor Wat’s builders or the expectations of those tasked with this tedious inventory is unclear.) Apsaras may seem an odd choice for renouncing the scopophilia of the 1st terrace since their aesthetic charms supposedly impart a spiritual bliss only hinted at by their voluptuousness. The 2nd terrace therefore should not be conceived as a place of deprivation but a higher level of pleasure above the carnal.

Apsaras are believed to be derived from animist nature spirits, not denizens of the element of earth (dryads) or water (naiads) but air, similar to the aurai in distantly related Greek mythology. As spirits of the wind, the Khmer associated them both with music and dance, especially from an unknown source, e.g. a breeze rustling through the leaves swaying the trees or the moaning of an Aeolian harp. When Hinduism supplanted animism in Southeast Asia, apsaras were assimilated into it, becoming one of the most common subjects of Khmer art. In the Hindu division of the world into trailokyas or three realms, apsaras hover above the gravity-bound world, and the chariots of victorious champions of divine writ, like Arjuna or Rama, similar to the "winged victories” or nikes with their tiny but exquisite temple on the Acropolis.

In Buddhism's translation of Hinduism’s tripartite division of the physical world into states of consciousness (by definition, illusory or maya,) apsaras inhabit a realm above even the devas or gods, who are still mired in the kamadhatu or “desire worlds,” possessing material bodies and seeking insatiably for external (cataleptic) pleasures. In contrast, despite their seductive depiction at Angkor Wat, Buddhist apsaras correspond with entities of the rupadhatu or "form worlds," who while still occupying space and time, find delight solely in their own radiance. Since they retain dimension or "territoriality" and experience emotion (albeit only bliss,) they have yet to attain the more elevated state referred to as “no taste” - the unconditioned, indifferent consciousness of the arupadhatu or "formless realms," the final steps towards nirvana, the extinguishing of consciousness itself.

Apsaras’ charms take on a different light in Vedic tradition, where they were the wives of half-animal, half-human nature spirits, gandharvas, the court musicians of the gods, whom they accompanied with dance. Their performance was no doubt made more intoxicating by their husband’s role as shamans responsible for distilling the elixir of immortality, amrta/ amrita (Sans.> immortal,) – or at least its feeling. The identity of soma has understandably attracted considerable attention among Indologists and seekers after “expanded consciousness.” Leading candidates include entheogens and hallucinogens, specifically sacrostemma acidum, indigenous to the Himalayas, as well as “performance-enhancing” drugs like ephedra sinica, aka “Mormon Tea,” a precursor to methamphetamines. As with so much else, there is no official record of the Khmer using soma or an equivalent – and all we have are official records. Still apsaras’ association with soma in Vedic lore suggests, they may have had a pharmacological basis beyond normal human wish-fulfillment displaced onto the immortals.

Apsaras, specifically in the form of the Apsara Dance, continue to play a central role in Cambodian cultural identify. Jayavarman VII is reputed to have employed (or enslaved) 3000 dancers at his court, however, there is no unbroken chain of transmission from these to the dances performed today which were invented only in the 19th and 20th Centuries with royal patronage. In possibly a unique example of the preservation of an ephemeral art form by one of the most enduring, over 1500 hand gestures (Sans. > mudra, Kh. > kbachs,) have been recorded and cataloged from apsaras depicted on Khmer monuments, a meaning assigned to each and these combined into dances, usually on themes from the still popular Ramayana (Kh.> Reamker,) the inspiration for so much classical Khmer art. Most of the "Apsara Dance's" kbachs as well as body movements inscribe flowing curves, supposedly reflecting the prominence of water in Khmer culture as the element of transformation, e.g. the less inviting naga or rainbow bridge..

Apsara dancers were obvious targets for the Khmer Rouge's campaign to erase every vestige of the past and build a society based on their precepts. The few survivors of their genocidal purgation of "incorrect ideas" have attempted once more to reconstruct this obliterated past, much as the Baphuon was pieced together after the Khmer Rouge destroyed the key to its anastylosis or, for that matter, the original invention of the Apsara Dance. Today these frames of an absent past embedded in stone are animated by the Royal Cambodian Ballet for audiences in their homeland and abroad, as well as, by local troupes around the world working to resuscitate this dance, the most transitory of art forms. Apart from Angkor Wat, the Apsara Dance is the most widely recognized symbol of Cambodian cultural identify and has been listed by UNESCO as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage, presumably not so much for its historic authenticity, as the tenacity of Cambodians and humans in general in re-establishing continuity, if only in imagination, with the irretrievably past.

APSARAS

APSARA DANCER, ROYAL CAMBODIAN BALLET (contemporary).

LIBRARIES

APSARAS, 2ND TERRACE, ANGKOR WAT (1113 -1150)

APSARAS, 2ND TERRACE, ANGKOR WAT (1113 -1150)

NORTH LIBRARY, 1ST TERRACE, ANGKOR WAT (1113 -1150)

The architectural values of the sthapakas and sthapatis who designed and built Angkor Wat may be clearer in individual buildings than the whole, which cannot be seen from any one perspective only by walking around it. The "libraries" (16, in the site plan below) in the northwest and southwest corners of the 1st (7,) outer and lowest terrace are by far the largest in Angkorian architecture, consisting of a nave and two aisles divided by double columns, with an eave above the aisles and a barrel-vaulted shala roof above the nave, the familiar split gavaksha or valabhi profile familiar from the meshes of Nagara (Northern Indian) shikharas and tri-lobed Khmer torana arches. Midway along the libraries’ long east-west sides are portals with pilasters and now-missing pediments and lintels, but no galleries, causeways, walkways or even a paved terrace links them to the rest of the monument; they sit like beached ships in the middle of the 1st terrace's broad sea of grass; one wonders how and if whatever they contained was used? Two more columns project to the east and west from the nave which support open porches on four columns, distyl porticos, each carved from single blocks of sandstone with chaste "Doric-like" capitals, reaching from the lower, level of the stylobate to the library’s eaves, the springing point for the porches' own, barrel-vaulted gables. The resulting roofline resembles a massive "staggered shala" aedicule, similar to the balanced sequence antarala > mandapa > ardhamandapa found at “linearly-expanded” temples also built during Suryavarman II's reign, such as Thommanon and Banteay Samre, except here the aedicular half-story is pierced by baluster clerestory windows. Like those temples, but to a much greater degree, these libraries rest on massive jagatis, (pithas, stereobates) divided into two identical sets of moldings, which set them further apart from their surroundings. Above these plinths, they have prominent, projecting upapithas (stylobates,) almost a second jagati, the height of a single set of moldings and a modest adhisthana (wall base) rising to the levels of the large baluster windows. The portals are reached by two flights of stairs corresponding with the jagati and upapitha. The jagati has four projections reflecting 1) the frontons of the stairs 2) the vessel or nave 3) the porticoes 4) the stereobate; hence the library is technically saptaratha.

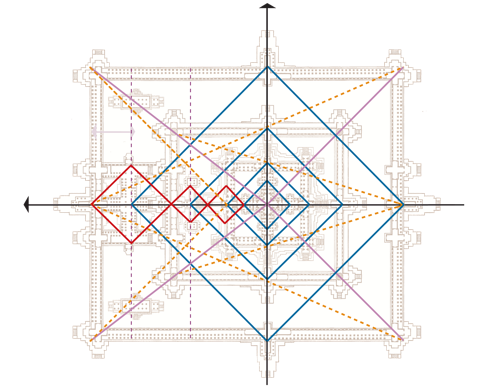

The entire structure possesses a symmetry and logic which to the western eye may appear classical, reminiscent of the Parthenon, if it rested on an Acropolis of its own making, or an Etrusco-Roman temple on its lofty pteron. This "classicism" is, of course, not derivative but the result of a shared demand for imperial and imperious order, symmetry and restraint with no place or need for additional embellishment. The libraries' horizontality, reinforced by the continuous bands of molding, extends the flow of the west-east axis across the wide expanse of the1st terrace’s (7) lawn between its galleries (8) and its cloister (13.). The center of their naves fall on diagonals linking the central tower with the western corner towers (14) of the 3rd and 2nd terraces as well as the corner pavilions of the 1st. These diagonals sew a net across the temple’s orthogonals binding its concentric terraces together and drawing them closer to the central tower (1).

FIGURE 18: DIAGONAL ALIGNMENTS, ANGKOR WAT (1113 -1150)

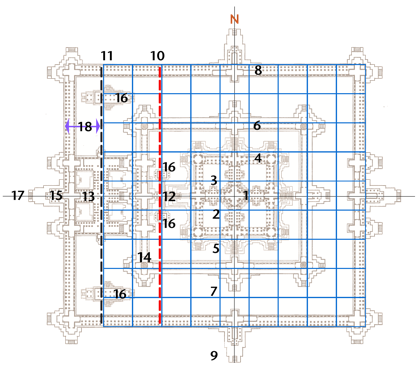

FIGURE 17: ANALYSIS OF SITE PLAN, ANGKOR WAT (1113-1150)

“CRUCIFORM CLOISTER”

1. Vishnu shrine and central tower

2. 3rd (upper) terrace

3. Cruciform pavilions (4)

4. 3rd gallery (open colonnade)

5. 2nd (middle) terrace

6. 2nd gallery (apsaras)

7 1st (lower) terrace

8 1st gallery (bas relief murals)

9. 4th (outer) enclosure

10. 2nd terrace “threshold line” (broken red line)

11. 1st terrace “threshold line” (broken black line)

12. 2nd terrace “cruciform walkway”

13. 1st terrace “cruciform cloister”

14. SW corner of double panthayatana of nine towers

15. 3rd west triple gopura (liturgical entrance)

16. “Libraries” (4)

17. Causeway over 4th (outer) enclosure and gallery from the moat

18. Eastward offset (13.4%)

9 x 9 = 81 pada paramasayika mandala

After passing through the 3rd wast gopura (15) and perhaps viewing the gallery around the 1st terrace (8,) a visitor would enter the three double colonnades and crossbar of the "cruciform cloister" (13) with basins in each of its quadrant. The crossbar corresponds with the “threshold line” (broken black line) of the 1st terrace (7,) the point where the terrace’s length and width equal a square in which a 9x9 paramasayika mandala (blue grid) can be inscribed. Though this cloister acts as an interruption of the west-east liturgical axis, there is no hard evidence what purpose this diversion may have served. It could have acted as a mandapa, a place to perambulate, congregate and contemplate in preparation for receiving the darshan of the wakened god. The colonnades could have contained shrines though there is no evidence of them; its columns are devoid of epigraphy, panels like the Baphuon or narrative moldings (mala) to provide a clue. When the temple became a Buddhist wat, the cloister’s colonnades were reportedly lined, no doubt hyperbolically, with "one thousand Buddhas," many of which are now housed in a room of that name at the National Museum in Siem Reap. There is no reason to believe, however, that the Theravada faith in rote repetition applied to Hindu polytheism. The basins might also have contained socles or pedestals like the balipithas in the 1st enclosures of Preah Khan and Banteay Kdei.

We cannot be certain that the basins were filled with water or used for ritual ablution since, like pradakshina, there is no evidence for this practice at Angkor. Precedents for this configuration of four basins can be found at temples already discussed, constructed at roughly the same time – the 1st enclosure divided into four quadrants of water at Banteay Samre, the four pools before the 1st enclosure at Phimai and the 2nd at Phnom Rung, the moat cut into four L's at Prasat Hin Muang Tam. There they represent the oceans surrounding Mt. Meru and the four "holy rivers" of India flowing from it. It would have been enough to the Khmer if the relationship had been symbolic; water represented an element of purification and of transition, both a barrier and bridge to be crossed on the way from the profane to the sacred. Despite these similarities the most compelling reason for believing the cloister’s basins were filled with water is the absence of a more convincing explanation.

“CRUCIFORM CLOISTER,” 1ST TERRACE, ANGKOR WAT (1113 -1150)

The climb between the “cruciform cloister” (13) and 2nd gallery (14) consists of three short flights of enclosed steps at the end of the three axial (west-east) colonnades. Entering them, the visitor is suddenly plungned from the sunlight of the cloister into the darkness of the stairwells, dramatizing the transition from the visual richness of the 1st gallery's murals and the shifting sight-lines of the open cloister to the optical austerity and claustrophobic spaces of the sober, inward-looking, 2nd terrace. This progress is marked by the four mounting barrel-vaulted roofs above each flight of steps, in effect, a "triple staggered shala" truncated by their intersection with the "double staggered shala" roof of the 2nd gopuras and gallery (6.) Four pediments, (including those at the end of the colonnades,) maintain the eastward and upward axial momentum of the three parallel corridors despite the lateral diversion offered by the 2nd gallery. This rise in levels is underlined by the repeating sequence of moldings from the base of the cloister's jagati (plinth) to the adhisthana and narrow ledge or sill beneath the 2nd gallery's blind baluster windows. Each of the three staircases leads into the 2nd gallery (6) which stretches to their right and left (south and north,) with a door ahead into the canyon-like 2nd terrace (5.) Only the central portal along the processional axis,leads to the elevated "cruciform crosswalk" (12) of the 2nd terrace.

STAIRS FROM 1ST TO 2ND TERRACE,

“CRUCIFORM CLOISTER”

ANGKOR WAT (1113 -1150)

“CRUCIFORM CROSSWALK”

CRUCIFORM CROSSWALK, 2ND TERRACE, ANGKOR WAT (1113-1150)

This photo from the top of the central steps leading to the 3rd terrace's western colonnade (4) shows the western, northern and eastern arms of the "cruciform crosswalk" (12) or “walkway” of the 2nd terrace (5,) its equivalent to the "cruciform cloister" (13) of the 1st and "cruciform colonnade" (4) of the 3rd. It is one of three cruciform structures linking the three terraces of Angkor Wat, though half the size of the other two and, as a composite rather than unbroken colonnade, can seem somewhat contrived. 1) Its western arm begins where the central stairs from the cruciform cloister reach the 2nd gallery (6,) extends across it and continues through the portal and porch projecting from the cruciform, central, 2nd west gopura (center rear of the photograph,) then along an elevated walkway until it intersects the crosswalk’s lateral arms. 2) The crossbar’s northern arm reaches from this intersection to the cruciform plinth of the 2nd terrace's northern library (16, at right.) The same configuration can be found on the east and west of the Baphuon’s 1st terrace. These two libraries are much closer in size and design to other Khmer “libraries” than those of the 1st terrace. 3) It is duplicated by a southern arm and library (16, to the left, out of frame.) The "threshold line" of the 2nd terrace (red broken line) falls on the edge of the crossbar, as it did for on the cruciform cloister of the 1st terrace. 4) The remaining eastern arm consists of the central staircase which rises at a 70° angle to a lip or platform protruding in front of the 3rd terrace's western colonnade (these stairs occupy the lower left of the photograph.) This "lip" is inserted to ensure that the 3rd terrace’s colonnaded gallery is centered on the shrine rather than off-set to the east like the 1st and 2nd terraces and their cloister and crosswalk. This solution is demonstrated in the diagram beneath figure 17 in the introduction.

The method employed at Angkor Wat for unifying its three terraces through cruciform structures to achieve the ideal of four-way symmetry seems overly complicated. It contrasts with a different solution adopted at the second major foundation of Suryavarman II's reign, probably completed by his successor but using many of the same artisans. Beng Mealea, located 40 km due east of Angkor on the road to Koh Ker and Preah Vihear, also consists of three concentric enclosures but all on the same level. It could be seen as the first "horizontal temple mountain," a design adapted for Jayavarman VII's (1181-1220) subsequent monastic complexes, Ta Prohm, Preah Khan and Banteay Kdei. At Beng Mealea, the three enclosures are joined by three continuous galleries running west from the triple, 3rd east gopura, the outer two become the peripheral corridors of the 1st (inner) enclosure while the middle one, along the liturgical axis, offers the sole entry to the sanctuary. Photographs of Beng Mealea, its site plan and analysis are the subject of the following section in this catalog.

“CRUCIFORM COLONNADE”

“CRUCIFORM COLONNADE,”3RD TERRACE, ANGKOR WAT (1113-1150)

The 3rd or upper terrace (2) is almost isomorphic with the “cruciform cloister” (13) of the 1st with three west-east colonnades and a crossbar. As revealed on the plan below, it is further sub-divided into an inner concentric square or diamond by four "pavilions" (3) midway on its crossbars; finally, four outer and four inner porches frame the square shrine (1) at its center. While the “cruciform cloister” is bounded by the outer towers of the 1st and 2nd triple west gopuras, signaling it as the beginning of the westward ritual axis, this “cruciform colonnade” is marked as a destination by the tower at its center and the double panchayatana of nine towers (14) centered on and punctuating its corners, as well as, those of the 2nd terrace (5) below. Its open double colonnade suggests that the similar feature on the 3rd terraces of the Baphuon (1061,) the temple mountain immediately preceding Angkor Wat, and Phimeanakas, the royal shrine (c.1000,) could not have been far from the architects’ minds. (It is impossible to know whether those temples’ lofty, destroyed towers were linked axially to their loggias as here.) Although this open colonnade provides spectacular views of the Angkorian plain especially after the “visual deprivation” of the 2nd terrace, it is doubtful that the terrace’s primary function was as a belvedere.

This cloister may have fulfilled similar, if undetermined, functions as the one of the 1st terrace, except for a higher, more privileged social strata, the monarch, his family counselors and their brahmins. The concentric subdivisions of the 3rd terrace might even suggest a hierarchy distinguished by proximity granted to the cult statue; the open colonnade (4) the furthest but most capacious; the pavilions (3) on the crossbars, antechambers for an inner circle, and the four porches before the shrine restricted to clergy and royalty. The purpose of the terrace’s four basins remains as much a mystery as that of their counterparts in the “cruciform cloister. “Filling them 171m above the ground posed a hydrological challenge the Khmer never attempted. As this photo shows, any monsoonal residue would have evaporated by January; one hesitates to imagine temple slaves carrying water up the 3rd terrace's precipitous staircases (though they carried the stones to build them.) The absence of a drainage system also militates against an aqueous solution.

What is perhaps most distinctive about this nine-chamber ensemble is the open, redented "peristyle" surrounding it, detailed on the plan of the 3rd terrace, above. It does not seem to have been intended for circumambulation since its 36 columns rest on different levels and can only be reached from the antarala and outer porches not the inner. Its function is most likely structural since it supports the immense shikhara. At the same time, it could be read as a continuation of the colonnades of the 3rd terrace's crossbars girdling the enclosed shrine; it consists of: 1) paired or off-set columns on the outer porch's plinth carrying the eaves, (equivalent to the central or axial rahu pagas or rathas;) 2) two columns beside the broader, higher inner porches (its intermediate anu rathas;) and 3) a single column beneath the corners of the square central tower (its kanika or karna rathas.) This pattern is then reversed until it reaches the two off-set columns of the outer porch of the adjacent arm of the crossbar. Like the redented, pancharatha garbagriha inside the square kostas (outer walls) of the shrine and tower, this peristyle is pancharatha as well. If the outer porches’ double, indented pairs of columns are counted as separate rathas, as is customary for a porch’s jambs or pilasters, the shrine becomes saptaratha, with seven rathas. This may explain the anomalous, extra rathas which appear in the cornice of the 1st tala of the superstructure between those corresponding with the outer porch.

PLAN OF THE 3RD TERRACE, ANGKOR WAT (1113 -1150)

The vertical ascent which begins at the cruciform cloister culminates at the finial of the shikhara or prang (1,) 42m above the floor of the 3rd terrace and 213m above the temple's plinth. Similarly, the liturgical path which starts at the 4th west gopura and proceeds through the 3rd west gopura and the three cruciform structures of its terraces culminates at the sanctuary beneath the shikhara, presumed to have held the statue of Angkor Wat's dedicatee, Vishnu, (now placed in the 4th enclosure's gallery.)The final climb from the western arm of the "cruciform colonnade" to the sanctum or garbagriha itself, parallels that from the cruciform cloister and the 2nd gallery, rising in three stages from the level of the crossbars and antaralas or vestibules linking them to the porches of the shrine. 1) The first is to a raised outer porch; 2) then to a higher, wider inner porch, half-emerged directly from the square prasat/ prasada/ shrine; 3) finally, to the jagati, the actual plinth on which the cella or garbagriha sits (in the photograph, this platform’s striated moldings can be glimpsed deep within the shadows of the shrine.) Each of the four double porches is covered by a broken or triple-lobed valabhi or split gavaksha roof with eaves, half-story and barrel-vaulted dormer with its own pediment.

CENTRAL SHRINE AND SHIKHARA, 3RD TERRACE,

ANGKOR WAT (1113-1150)

The three flights of steps between the three levels of the shrine and the three staircases between the "cruciform cloister" and 2nd terrace could be compared with the Hindu division of the world into triklokahs or three realms – earth, sky and heaven. They would thus duplicate in miniature Angkor Wat's own three terraces (3,5,7) and the geography of Mt. Meru on which it is based. The lateral and axial expansion of the monument can be traced outward from the central shrine's axial projection of 1) the four inner porches, 2) the four outer porches, 3) the four arms of the 3rd terrace’s crossbars, 4) the four medial pavilions 5) and the eight lateral projections of its dipteral square colonnade, 6) the axial and lateral “cruciform crosswalk” and “cruciform cloister” on the 2nd and 1st terraces, 7) the lateral extensions of the 2nd and 1st galleries 8) out along the causeway of the 4th enclosure to the Khmer lands beyond.

BEYOND ANGKOR WAT, REMAINS OF ITS NETWORK OF WATERWAYS

Angkor Wat, the "city in the form of a temple," extended its sacred geometry into its 4th enclosure through the grid of streets in which its citizens lived and worked and across its moat to the intensely, cultivated wetlands around it. This floodplain of the Tonle Sap's annual reflux left the land so fertile and irrigated it could support two rice crops a year and a regional population estimated as high as 500,000. Recent LIDAR imagining, as already noted, has revealed an extensive, orthogonal network of canals oriented in accord with the city and the temple's axes, theorized to have been used for crop irrigation and shipping while the great barays may have been reserved for potable water and recreation. This grid may help explain the puzzling spacing and decentralization of monuments found in today's archaeological park; Angkor Wat may have been a large, low density conurbation like the Aztec Tenochtitlan. Only a small part of this riparian system is visible on the surface today; an example is this pleasant basin immediately across the main thoroughfare parallel to the moat and 4th enclosure of Angkor Wat and continuing north to Phnom Bakheng and Angkor Thom.

66