PREAH KHAN ( 1191)

PREAH KHAN ( 1191)

20 THRESHOLDS: FROM PROFANE TO SACRED & BACK

The following commentary and photographs supplement the discussion of Preah Khan in section XIII, “Axial Diffusion, Confusion and Illusion” of the introduction to this site and illustrate the analysis of its site plans, figures 20 and 21. Those pages contain a “close reading” of this temple monastery to ask how (and if) Jayavarman's VII's ambitious program to rebuild the Khmer Empire as a Buddhist state found architectural expression in the unprecedented innovations of this and other of his religious foundations.

Preah Khan was the most ambitious of all Jayavarman VII's monastic foundations, honoring his father Dharanindravarman II (r.1150-1160,) identified posthumously with Avalokitesvara (Kh.> Lokesvara,) the Mahayana "bodhisattva of compassion,” (just as Ta Prohm associated his mother with Prajnaparamita, the "goddess of wisdom.") According to the temple's unusually full, not to say fulsome, dedicatory epigraph, it was built on the site of Jayavarman VII's victory over the Cham which brought him to power and reunified the Khmer Empire in 1181. In recognition, the temple was consecrated to no fewer than 430 deities for whom its resident monks conducted ceremonies on 228 days of the year. To its east, Jayavarman VII constructed his own 3.5km by .9km Jayatataka Baray to provide the complex with a dedicated supply of water and also surrounded it with an 800m x 700m 4th enclosure to house the monks, dancers, musicians, artisans and servants needed to operate this de facto Buddhist university, a Cambodian Nalanda, coincidentally built at almost the same moment the Islamic Delhi Sultanate destroyed the original in Bihar.

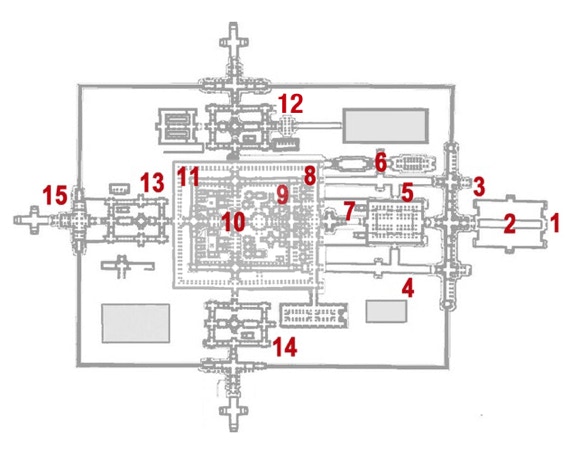

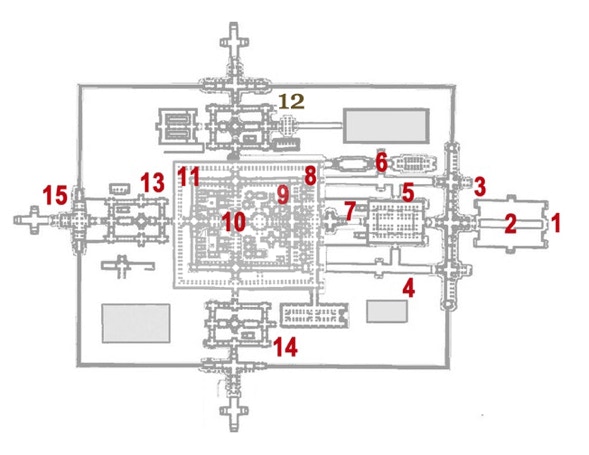

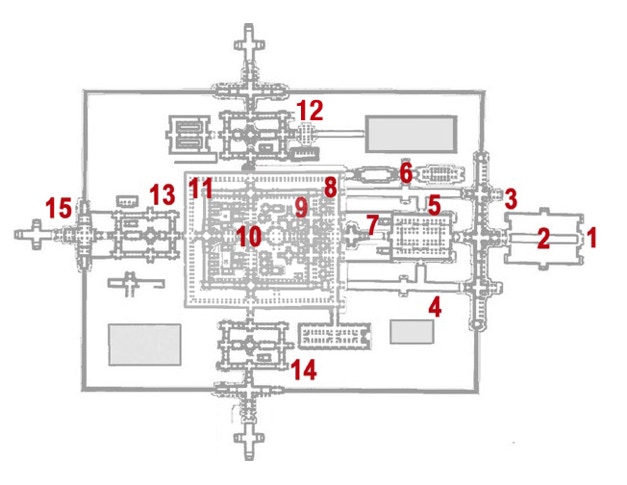

As elsewhere in this anthology, the thirteen photographs in this section have been arranged roughly in the order a visitor would encounter them moving along the temple's east-west axis (which can be traced on the site plan below using the key. In the case of Preah Khan, this seems especially appropriate since the gopuras, portals and concourses which comprise its extended processional path are aligned to give an unbroken view across its kilometer-long course. It begins on the east with a 200m causeway from the Jayatataka Baray, crossing a naga bridge and moat before passing through the triple-gated, 4th east gopura, guarded by seventy-two garudas, Vishnu’s bird-man vihana, mount or vehicle, veh(to the right off this site plan.) It then proceeds through the 4th enclosure (1,) past its “House of Fire,” over a terrace (2,) through the 3rd enclosure’s wall and gopura (3,) into the 3rd enclosure (4) with its "Hall of Dancers" (5) and unique, two-story building (6.) It next enters the protruding 2nd east gopura (7,) passing through the portico and shrines (8) filling the east of the 2nd enclosure, through the central portal of the 1st east gopura into the 1st enclosure (9,) down an enfilade lined with small shrine, until it reaches the somewhat anti-climactic central shrine (10.) It then retraces its steps in reverse order past the crowded western courtyards of the 1st enclosure, across the dipteral peristyle around the narrow 2nd enclosure (11,) down the central or liturgical corridor of the western ”Vishnu" sub-temple (13,) leaving the temple though the 3rd (15) and 4th west gopuras before disappearing into the surrounding forests. In traversing this axis, a visitor cross more than twenty thresholds between discrete spaces, each presumably representing a different level of spiritual attainment or filling a specific ritual purpose.

Key to Site Plan: Preah Khan

1 – 4th enclosure

2 – Terrace

3 – 3rd enclosure wall and gopura

4 – 3rd enclosure

5 – “Hall of Dancers”

6 – Two-story building

7 – 2nd east gopura

8 – 2nd enclosure shrines

9 – 1st enclosure and gallery

10 – Central shrine

11 – 2nd enclosure and peristyle

12 – Shiva sub-shrine

13 – Vishnu sub-shrine

14 – Ancestors’ sub-shrine

15 – 3rd west gopura

SITE PLAN, PREAH KHAN (1191)

The causeway from the Jayatataka Baray ends at a moat crossed by a naga bridge (below,), the traditional Khmer symbol for a passage from earth to air and profane to sacred space. It was lined with parallel rows of devas and asuras, like the bridge to Angkor Thom’s south gate, dramatizing the central Khmer myth, "The Churning of the Ocean of Milk," the Samudra Manthan, recounted on countless lintels. The heads of both gods and demons have been looted to provide garden ornaments and decorations for museum galleries and their patrons. Boundary markers or sema line the causeway; two are visible to the left of the rearing naga, carved as vyala or yali, leogryphs with the head of a lion, the torso of a human and the legs of a garuda, a bird. They were originally capped by niches containing Buddhas, subsequently defaced by the brahmanic revanchism of the 13th Century.

To the north of this causeway is a large "House of Fire," (at right,) whose actual function, like that of the "libraries," remains conjectural. Nonetheless, its basic form is replicated by no fewer than 121 similar shrines along many of the empire's highways: a tower on the west and nave on the east, like a temple, with windows only on the south and unusually thick walls (perhaps as fire retardants!) It is thought to have contained the "ark of the sacred flame," a uniquely Khmer institution which may have pre-dated both Hinduism and Buddhism. It is a regular feature in the murals representing military processions at both Angkor Wat and the Bayon and seems to have been carried into battle as a kind of palladium.

"HOUSE OF FIRE," 4TH ENCLOSURE,

PREAH KHAN (1191)

NAGA BRIDGE, 4TH ENCLOSURE, PREAH KHAN (1191)

The 4th enclosure's laterite walls (at right) are faced with seventy-two, 5m tall relief sculptures of garudas standing on their traditional foes, the nagas, holding up their tails in triumph. Nagas may have provided a liquid bridge from earth to air but they seem to have had no place in an enclosure where monks shed the illusions of physical reality (though nagas too shed their skins.) Garudas, however, as aerial creatures, could more easily be assimilated into the realm of the enlightened, the bodhisattvas and the disembodied entities of the arupa- and rupadhatu. Here, the bird-men can be interpreted as literally lifting the temple off the ground, the Angkorian plain and terrestrial plane, in a Buddhist inversion of "flying palaces," carrying their human inhabitants not to Mt. Meru but the heights of consciousness and beyond. .

GARUDA, 4TH ENCLOSURE WALL,

PREAH KHAN (1191)

A PROFUSION OF FORMS

APSARA FRIEZE, DETAIL, “HALL OF DANCERS,” PREAH KHAN (1191)

Preah Khan would be seen as an extreme experiment in Jayavarman VII's unorthodox architectural corpus were it not for the Bayon where he outdid himself and almost everyone else. The trend in Khmer architecture, epitomized by Angkor Wat's three terraces, had been towards reducing the types and number of temple parts and their consolidation into the most concise and symmetrical possible configuration. In contrast, Jayavarman VII appears to have reveled in innovation; more new forms were invented (and usually abandoned) in his reign than in the preceding three centuries of Angkorian temple construction. Under him, the Khmer cultivated an almost Mannerist “architectural language,” self-consciously flaunting convention, combining familiar architectural tropes surprising ways, as if novelty were an end in itself. In Preah Khan’s 3rd enclosure, introduces a profusion of new forms whose functions are elusive and continue to pose conundrums for archaeologists and art historians.

"HALL OF DANCERS," 3RD ENCLOSURE,

PREAH KHAN (1191)

“HALL OF DANCERS,” PREAH KHAN (1191)

The “Hall of Dancers” measured twelve columns long by eight wide, divided by three east-west corridors and a north-south crossbar or transept, bordered on their inner sides by dipteral colonnades, forming four small pillared courts between them. This arrangement may be related to the cruciform eastern building in Beng Mealea’s 3rd enclosure, as well as, the three other sub-shrines at Preah Kkan. These four rectangular "courtyards" are sufficiently enclosed to have been left open like atria but could also have been easily spanned by overlapping stone slabs, like a mandapa. At the photo's top, a corbelled arch once carried a shala roof over the nave or central corridor. This central concourse was connected with the 2nd east gopura (7,) which peculiarly protrudes in front of, rather than through, the 2nd enclosure, as would be logical for a gate. An explanation for this might be to join the "Hall of Dancers" and 2nd east gopura (7) as closely as possible in a continuous corridor across the 3rd enclosure, equivalent to the central gallery or nave of the Vishnu shrine (13,) its counterpart on the west. Just as the sub-shrines’ enclosed middle galleries are flanked by galleries to their north and south, two outside walkways parallel the central corridor of the "Hall of Dancers" aligned with the stairs to the peristyle and eastern shrines of the 2nd enclosure (8) and the north and south galleries of the 1st or inner enclosure (9.) This fusion was first seen between the “cruciform cloister” and 3rd terrace at Angkor Wat, (though broken by the 2nd terrace,) and in uninterrupted form at Beng Mealea. At Preah Khan, however, like Ta Prohm, there is no gap on the central or liturgical concourse west of the shrine and axial crossing, rather it continues through to the temple's 3rd west gopura (15) and beyond.

The 3rd east gopura (3) is the major entrance to Preah Khan and includes an unprecedented five entrances separated by galleries with outward-facing colonnades. Leaving this 3rd east gopura the east-west axis passes through a hypostyle building of the type generally identified as a "Hall of Dancers" (5.) It was probably fenestrated like the one at Banteay Kdei and its three, similarly proportioned and geometrically positioned companion shrines on the 3rd enclosure's north, west and south axes (12,13,14,) dedicated respectively to Shiva, Vishnu and the Khmer kings. Its identification as a "Hall of Dancers,” a nata mandira or rangamandapa, a platform or stage for sacred dances, is strengthened by the building's many lintels featuring acrobatic apsaras who contrast with the more graceful, poised celestial nymphs in Angkor Wat's sober 2nd gallery where there is no place for”flesh and blood” court dancers. A hypostyle hall would seem to place restrictions on the kind of dancing it could accommodate, perhaps just single dancers posed in the interstices between its columns, their movements limited to sinuous poses and hand gestures (kbach) like today's Apsara Dance, which was, in part, reconstructed from these same friezes, like the detail above. The empty niches over it in the view at left contained Buddhas before Jayavarman VIII's (1243-1295) Hindu iconoclasm defaced them.

TWO-STORY BUILDING, 3RD ENCLOSURE, PREAH KHAN (1191)

The most notorious example of a building at Angkor which is both strikingly original and has also resisted credible explanation can be found on a terrace just north of the “Hall of Dancer’s.” No doubt its celebrity derives, in part, from its initial evocation of a structure from Classical Antiquity (which dissipates upon closer scrutiny.) The building's (6) vessel (“nave” or “naos”) is an open-sided hypostyle hall, four columns wide (tetrastyle) and six long or dipteral (with two columns along each side of its pteron or stylobate. It has two-column deep porticos attached to both ends of six columns wide projection (avant-corps or risalti) forming four aisles and a wider central concourse. (At first glance, the outline of the building might suggest Palladio's Palazzo Chieracati (1554) in Vicenza.) It is the only Khmer building with two full (not aedicular) stories. Therefore, it comes as a surprise that there are no signs of joists or brackets to support a second floor nor stairways, ramps or ladders to get there. Khmer masons used single blocks of sandstone, for the tall one-story porticos of the libraries on Angkor Wat's 1st terrace; here. however, they employed the more tectonically sound solution of a single-story stack of drums with an architrave, which then repeated. The theory that the building's height was necessary

for a granary or hayloft is belied by its open sides, to say nothing of its architectural ostentation. The Khmer were certainly capable of building enclosed towers, but they left no stone silos.

This structure seems even more anomalous when one notes that the nave's "second story," clerestory walls are shorter than the columns of its porticos, as are its pediments. This suggests the nave had a lower barrel-vaulted shala roof than the porticos, the opposite of the usual “stagger,” (projecting a second roof from under a taller one.) Thus, the building might be read as a play on a standard, two-story, rectangular shala shrine aedicule, its end-on panjara arches covered not by nasis or gadha windows but by Khmer pediments. It is also noteworthy that this building’s columns are round not square, suggesting an early13th Century date; if true that would prove that the octogenarian Jayavarman VII had lost none of his taste for innovation.

This still does not explain the need for two-stories. The dense intercolumniation of the side aisles left scant space for storage, statues, shrines, sacred dances or other rituals but could at most have accommodated spectators for a

“THE SPIRIT OF CONFUSION”

The apparent jumble of Preah Khan's three, inner enclosures (4,11,9) graphically illustrates what Maurice Glaize, the eminent EFEO archaeologist, described as the "spirit of confusion" – "confusion" qualified as “spirit,” ,esprit, élan, flair or Jayavarman VII's other temples. By this, the scholar conveyed not just his reservations but also the sense of a rejuvenation for the old and recently humiliated Khmer Empire which may have permeated the optimistic, opening decades of that monarch's long reign (1181 -1120.) These decades appear to have also been a time of openness to experimentation in religion, statecraft and the buildings which reflected them (followed, as so often, by an embittered reaction.)

1 – 4th enclosure

2 – Terrace

3 – 3rd enclosure

wall and gopura

4 – 3rd enclosure

5 – “Hall of Dancers”

6 – Two-story building

7 – 2nd east gopura

8 – 2nd enclosure shrines

9 – 1st enclosure and gallery

10 – Central shrine

11 – 2nd enclosure and peristyle

12 – Shiva sub-shrine

13 – Vishnu sub-shrine

14 – Ancestors’ sub-shrine

15 – 3rd west gopura

FIGURE 20, SITE PLAN, PREAH KHAN (1191)

rite or a procession, passing down the broader central corridor and out into the enclosure. Why one might ask, were there two porticos and no apse? Whatever was in the building or passed through it could enter or exit at either end .The height might be explained, if it were used for storing or parading ritual paraphernalia taller than a single-story column. A cursory review of Khmer murals shows that parasols of honor and battle standards are the only common objects which poke their bobbing heads above the monotonous rows of soldiers, elephants and palanquins in every military parade. Could the building have been a repository for the standards won or carried during the battle on this same site marking the start of Jayavarman VII's reign? A speculation substantiated by absolutely no evidence.

This survey of Angkorian temple mountains has proposed (too often) that, prior to the watershed of 1181, a trend towards consolidation and integration of Khmer architectural vocabulary and grammar leading to larger and more cohesive monuments reached its apogee at Angkor Wat. With Jayavarman VII, a countervailing centrifugal force seems to have asserted itself; the 3rd enclosure at Preah Khan (4, on the site plan above), for example, is sprinkled with nine shrines and five pools which beyond their orthogonal orientation do not appear to fit within any larger design. The 2nd enclosure (11,) reduced here to little more than a vestibule to the 1st (9,) still manages to squeeze eight shrines, four multi-chambered gopuras and a forest of columns along its eastern edge.) The 1st enclosure (9) crowds two 13-chamber, three 8-chamber and one 3-chamber gopuras, an incomplete gallery with a less complete pteron around its inside, plus four irregular courtyards, four mandapa-like pavilions, a 7-part central shrine (10) and up to forty-eight individual shrines and sub-shrines into the smallest of the temple's six "horizontal terraces” (9.) Furthermore, as the diagonals in figure 20 of the introductiondemonstrate, the 1st and 2nd enclosures' dimensions were determined by features in the 3rd enclosure rather than an overall plan for what they might go inside of them.

This inclusiveness, bordering on the indiscriminate, may have been a consequence of Jayavarman's VII's apparent receptiveness and tolerance towards pluralistic religious currents despite their doctrinal differences. Since these shrines were constructed piecemeal over decades, they suggest that monarch's religious curiosity or indulgence of his subject's heterodox beliefs did not abate. In the absence of more specific knowledge of daily Angkorian religious practices, however, we cannot be certain that these later additions were not revisions signaling a retreat to orthodoxy.

Preah Khan's north-south axis, like its east-west, consists of a series of alternating colonnades, bridges, gopuras and shrines with portals aligned to give an uninterrupted view across the three inner enclosures. This view from the sub-temple to the Khmer kings on the south (14) continues past the central shrine to the Shiva temple (12) on the north and out the exceptionally long 3rd north gopura deep into the 4th enclosure (1.) Along its course, this axis crosses more than 20 thresholds marked by raised door frames and steps which would seem to make a direct procession to the central shrine (10) unlikely, if not undignified, and suggests pauses at some of these interstitial spaces for rituals or meditation. The exact location of the central shrine with the cult image of Buddha is lost among this corridor's shafts of light and shadow, which might leave the impression of an indistinct but incremental path through multiple spiritual states before becoming lost or one with the blinding light of enlightenment.

NORTH-SOUTH AXIS, PREAH KHAN (1191)

3RD WEST GOPURA, PREAH KHAN (1191)

The 3rd west gopura (15; photo above) lacks the five portals of its eastern counterpart (3) but its seven staggered roofs still comprise a balanced and dignified ensemble. The gopura illustrates both "lateral and axial" expansion: 1) a square tower extends four arms with one window each to form a cruciform, central chamber; 2) this then projects four porches: the larger western portal (at the photo's center) and two lateral extensions to its right and left (south and north,) each with two windows, marked by roofs at a lower level; 3) next these two are laterally extended again a step lower with a blind, baluster window and the gopura's north and south portals with their own dvarapalas. Each of these sections is lower and more recessed than the previous resulting in a “triple staggered shala” roof profile, broken by the western porch and shikhara, in place of a nasi or panjara. Only the central of the three portals has an eastern porch to connect it with the unbroken axial corridor down the center of the western Vishnu shrine (13) and from there back along the entire axis to the east.

BALIPITHA OR SOCLE, NW COURTYARD,

1ST ENCLOSURE, PREAH KHAN (1191)

The 3rd west gopura’s (15 west-facing portal, unusually, is framed by jambs of “giant order” columns reaching not to the eaves and cornice of the galleries’ doors and windows but the cornice of the aedicular half-story of the cruciform central chamber. This required larger-than-life size dvarapala or door guardians beside it which have since been decapitated, (not for any possible Buddhist leanings, simply because they were too large to loot in one piece.) The square columns behind them are adorned with simple annulets (tati, necking,) echinus (mandi) and square abacus (phalaka or plate) which support a simple architrave in lieu of a carved lintel.

The torana arch at the gable’s end is covered by a pediment depicting a scene from the Ramayana, the climactic "Battle of Lanka." On the left, Rama in his chariot draws his bow to loose the fatal arrow which will kill Ravana, easily identifiable on the right by his twenty, flailing arms, thereby ending his threat to dharma and recovering his wife. At the apex of the pediment, Vishnu tips the battle in favor of Rama, the paragon of righteous kingship and his 8th avatar (by some counts.) Hanuman and his monkey troops, who have played a decisive role in the war, perform acrobatic feats around the arch’s three lobes. Curiously, the central combat is not at the center of the pediment; rather a god stands above it in triumph on top of a makara (a sea monster or dragon, thought to have been inspired by crocodiles.) It is the vahana or vehicle of Varuna, god of water, who plays at best an equivocal and minor role in the epic, at first refusing, then relenting to help Rama build the bridge to Ravana’s island, Lanka (Sri Lanka.) The marine allusion may refer, albeit indirectly, to Jayavarman VII’s own victory in the “Battle on the Lake,” depicted on the south face of the Bayon’s 1st terrace, so perhaps, he not Varuna is shown – not over but on the sea. Rama’s defeat of Ravana draws an obvious parallel with Jayavarman VII's victory over the Cham on the site the temple commemorates. The pediment is characteristic of the "Bayon style" of relief carving –- angular and somewhat tangled, rather than rounded and flowing as at Angkor Wat, packed with as many incidents as possible, but lacking a cohesive design, rather like the temple where it marks the last threshold.

In addition to Preah Khan and Ta Prohm, Jayavarman's VII's also founded three smaller monasteries in the forests around the Jayatataka Baray — Banteay Kdei, Ta Nei and Ta Som — the temples which follow in this anthology. Despite the sangha of resident priests, Preah Khan, like the hostels of earlier "temple mountains," probably made some provision for wandering hermits who offered an alternate, soteriological path in Indic religions pre-dating Buddhism. Buddha himself gained enlightenment while pursuing the path of a Hindu sramana or individual seeker of truth in the wilderness around Bohd Gaya. Shiva Bhikshatana pursued austerities among outcastes and in polluted places which have been theorized as providing models for some of Tantric Buddhism's more controversial practices. “Forest monks" and the hermit’s path to enlightenment form the subject of Appendix VII to this catalog’s introduction.

The Hindu rishis or Buddhist bhikkus, pictured at right, are "forest monks" seeking their way to salvation in solitude among the undergrowth but free from the entanglements of a settled life. Their floral niches represent the caves and wattle hutches of sadhu who vow to use only such shelter as nature provides them. The figures above them are shown through a common Khmer convention for perspective - not in but behind the trees around the figures in the foreground. This panel is as much an incised frieze as a sculpted mural, as decorative as descriptive; it shows its makers' delight in recording minute, naturalistic details, such as the long-tailed monkeys plucking pineapples (or coconuts) from the branches, a playful detail characteristic of Bayon art but out of place in the more idealizing ambience of Angkor Wat. By depicting every leaf more precisely than it could be perceived in dense foliage, the panel might suggest medieval tapestries and illuminated manuscripts or the "innocent" eye of so-called "primitive," untutored or "outsider" artists. But this "naïve" hyper-realism reveals an order behind what might otherwise appear a chaotic wilderness, thereby revealing the workings of a higher nature. Similarly, absorption in a decorative pattern like these rishis suggests a life in harmony with a universal order or all-encompassing absolute.

FRIEZE, 1ST ENCLOSURE, PREAH KHAN (1191)

“THE BATTLE OF LANKA,” 3RD WEST GOPURA, PREAH KHAN (1191)

69