BANTEAY KDEI (1181 - 1220)

BANTEAY KDEI (1181 - 1220)

TERRACE WITH NAGA BALUSTRADE, 4TH ENCLOSURE, BANTEAY KDEI (1181 - 1220)

Banteay Kdei, resembles Jayavarman VII's (1181-1220) two other large, monastic foundations, Ta Prohm (1186) and Preah Khan (1191) though at a more modest scale and with a more readily comprehensible plan. No dedicatory inscription has been found; some archaeologists believe the temple may have been one of that monarch’s first projects, citing similarities with the Angkor Wat style, while others believe it was an outgrowth of his earlier and larger undertakings, dating after 1200 during the waning years of that king’s lengthy reign. In either case, the temple might provide “brick and mortar” evidence of how, and if ,the shift from Hinduism’s rituals, sacrifice, darshan, puja and bhakti (emotional attachment to personified deities) to Mahayana Buddhism's emphasis on life-long spiritual development through systematic mental and physical disciplines like meditation and yoga, changed Khmer temple architecture over the forty years Jayavarman VII put his personal stamp on every aspect of Khmer life.

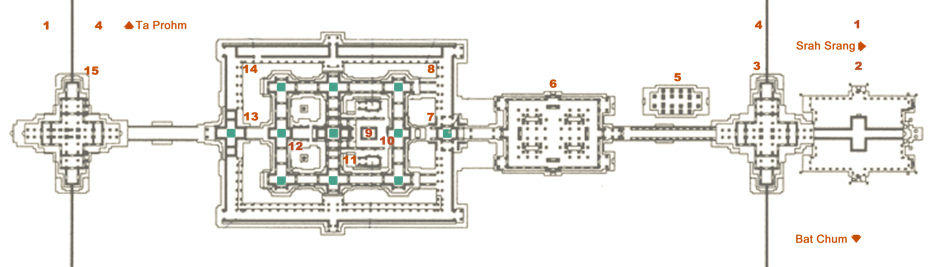

The northwest corner of Banteay Kdei's 4th (outer) enclosure wall is tangent to the southeast corner of Ta Prohm's 5th (outer) enclosure wall, underlining the close links between these two complexes. A pathway leads from a landing stage on the Srah Srang baray, north of Bat Chum temple (c. 960,) to the 500m x 700m outer enclosure with its four gopuras each with Jayavarman VII's signature "face tower.” As at that monarch’s two prior monastic temples, this outer enclosure supplied the practical necessities for the community of resident monks. From the 4th east gopura, a 200m causeway passes two shrines, a "house of fire" and one of Jayavarman VII's "hospitals" or "hostels," before reaching a cruciform terrace and naga rainbow bridge (2 on the site plan below; pictured above,) guarded by rearing nagas and simhas or chinthes which lead across the moat surrounding the temple's 3rd enclosure (4.)

“THE CITADEL OF CHAMBERS”

Compared with Ta Prohm and Preah Khan, Banteay Kdei's site plan (below) can appear a model of coherent planning and modest ambition. The temple’s architecturally evocative name, “The Citadel of Chambers” or “of Monks’ Cells,” emphasizes that its spaces were specifically designed for the contemplative life of a Buddhist bhikku. The identical, cruciform 3rd east and west gopuras (3,15) are Greek crosses with four columns dividing each of their arms into a short nave and two aisles. These arms in turn project four porches and two outer porches on the north and south which connect with the enclosure wall, while on the east and west, two-column deep porticoes cover the liturgical axis. These lead into the spacious 3rd enclosure (4) containing only two buildings – both on its east: a) an open, hypostyle shrine (5; pictured at right) with a tetrastyle nave or naos (four columns wide and long) with porticos on single columns at either end, similar in outline and position to the more celebrated, two-story building at Preah Khan but half its size and height; and, b) further west along the axis, a "Hall of Dancers" (6) like those at the two earlier temple monasteries. An elevated walkway continues a short distance west to the 2nd east gopura (7) with side patios which lead to openings in the 2nd enclosure’s(8) wall to its inward-facing, dipteral peristyle (14,)

OPEN TETRASTYLE HALL, 3RD ENCLOSURE, BANTEAY KDEI (1181 - 1220)

KEY SITE PLAN, BANTEAY KDEI (1181-1220)

9 – "Mandapa" (with enclosed room)

10 – 1st east gopura

11 – 1st enclosure

12 – 1st west gopura

13 – 2nd west gopura

14 – Dipteral portico and blind gallery

15 – 3rd west gopura

– Shikharas (towers, 11)

The 2nd east gopura (7) consists of a cruciform chamber with north and south porches encased in four L-shaped rooms which connect to the 2nd enclosure’s peristyle (14) and a portico between the very close 1st and 2nd east gopuras (7,10.) This encases the gopura’s cruciform central chamber in a second cruciform structure, a minor trope at Banteay Kdei of “rooms-inside-rooms,” whose closest equivalent in Khmer architecture is the Bayon’s 1st east gopura and the enfilade of structures leading from it to the central shrine, detailed in figure 24 of the introduction to this catalog.

The 2nd enclosure's peristyle (14,), dipteral on its east, south and west, but peripteral (single-columned) on the north where it forms a kind of portico before two blind galleries with doors and porches at their centers, which constitute the inconspicuous 2nd north and south gopuras. Similar inward-facing pterons before blank walls surround both the inside of the 1st gallery and 2nd enclosure wall at Preah Khan. Both are puzzling since they open only onto the narrow space between them and the blind galleries of the north and south galleries of the 1st enclosure; in a sense, they rather futilely lead only around themselves.

As at Beng Mealea, the gopuras of the 1st (10,12) and 2nd (7,13) enclosures at Banteay Kdei are fused together by porches and porticoes shrinking the 2nd enclosure (8) and its peristyle (14) to little more than an alley around the 1st 11.) Also, as at Beng Mealea and Preah Khan, the 1st enclosure's north and south galleries are extended to the 2nd’s, forming the small courtyard between them, which was so important to the geometry of Beng Mealea. Unlike Preah Khan, however, these north and south corridors are not continued as elevated walkways beside the "Hall of Dancers" (6) and across the 3rd enclosure (4,) as they easily could, but dead end in the 2nd gallery, just steps from the opening in its wall to the patios before the "Hall of Dancers” (6.) On the other hand, unlike Beng Mealea, Banteay Kdei's east-west and north-south axes do not stop short of the central shrine at the gallery of the 1st enclosure (11) but, as at Preah Khan and Ta Prohm, continue uninterruptedly to the 1st and 2nd west, north and south gopuras.

1 – 4th enclosure

2 – Terrace with naga balustrade

3 – 3rd east gopura

4 – 3rd enclosure

5 – Tetrastyle (four-column wide) building

6 – "Hall of Dancers"

7 – 2nd east gopura

8 – 2nd enclosure

NORTH - SOUTH AXIS, 1ST AND 2ND ENCLOSURES,

BANTEAY KDEI (1181 - 1220)

NORTHWEST TOWER, 1ST ENCLOSURE,

BANTEAY KDEI (1181 - 1220)

DVARAPALA, 1ST ENCLOSURE,

BANTEAY KDEI (1181 - 1220)

The compression of its 1st and 2nd enclosures (11,8) brings the temples 11 towers (green squares) closer together: a) two over the 2nd north and south gopuras, b) the four over the axial gopuras of the 1st enclosure (11) and c) four more over that enclosure's (intercardinal) corners; thus their distances from the central tower have a ratio of 2:√2:1, adding to the sense of compression. This results in an unusual configuration: a cross with three, equal crossbars and a panchayatana (quincunx) of towers sharing their center, fusing the 11 towers (green squares) into a unified group. They also outline an irregular hexagon with a strip of five towers down its middle, so that from any perspective along the east-west axis, they appear superimposed minimizing their linear distance from each other and contributing to the sense of single massif.

The 1st enclosure (11) at Banteay Kdei consists of an enclosed, rectangular outer gallery or cloister divided into four courtyards or garths by two crossbars, (galleries or enfilades,) connecting its four cardinal gopuras with the central shrine and shikhara. The courtyards on the east are as usual "linearly extended" to accommodate a "mandapa" (9;) here, however, that hall connects directly to the western arm of the 1st east cruciform gopura (10.) The mandapa itself is three aisles wide; the outer two connect with the central shrine's north and south porches and the cross-axis The wider, middle aisle along the east-west liturgical path, however, is obstructed by a square, enclosed chamber at its center (9,) so the mandapa no longer functions as an open assembly hall before the shrine but creates its own sacral space with an ambulatory around it, another "room-within-a-room" like that of the 3rd east gopura (3.)

The central shrine can only be reached from the privileged eastern direction by going around this square (9) and through the sanctuary's eastern porch which is partitioned from the mandapa's north and south aisles. These two side aisles and the north and south porches of the cella, offer routes around the central shrine to the enfilade of the north-south axis and thence to the galleries of the 1st and 2nd enclosures (11,8.) Again the closest parallel – not only structurally but possibly temporally – is the sequence of enclosed chambers at the Bayon which fragment and restrict progress along the liturgical axis to the cella.

The mandapa's (9) western counterpart on the liturgical axis is an enclosed oblong chamber, similar to the one west of the central shrine at Ta Prohm, rather than the open hypostyle pavilion at Preah Khan. The northwest and southwest courtyards, however, share with the latter temple central balipithas, pedestals or socles, probably bases for altars, aligned between the shrine's center and the 1st enclosure's western corner towers. Otherwise, these courtyards are spared the gallimaufry of small shrines which crowd their counterparts at Preah Khan.

The site plans of the temple consulted differ in small details. In the one shown here, for example, the two “libraries” are identical; in a second, more widely reproduced plan, a small room or bay protrudes from the mandapa's south side but not its north; while, in a third, the two libraries are also identical but both are attached to the mandapa by two porches and to the 1st enclosure's north and south galleries by a crosswalk, forming a second crossbar across the eastern courtyards, parallel to the north-south crossbar through the central shrine. The poor condition of the temple no doubt accounts for many of these discrepancies but the capriciousness of so many of Jayavarman VII's projects means archaeologists cannot rely on regularity or precedent.

All the site plans concur in one respect: they show passageways or gaps between the two enclosure’s (11,8) galleries and their courtyards other than the orthogonal paths prescribed by the gopuras, galleries and axes – though, predictably, they do not show these in the same places. For example, on the site plan above, there are four breaks in both the east and west walls of the 1st enclosure (11) and doors on one of both sides of the four short galleries linking the nine cruciform towers (green squares,) providing direct access from the 2nd enclosure to the courtyards of the 1st as well as among them without passing through the central shrine. It also shows four entrances between the 3rd and 2nd enclosures (4,8) at the corners of the latter, as well as the cardinal axes. In other plans, however, doors are shown to both the right and left of the 2nd east and west gopuras' (7,13) porches Given the condition of the temple, it would not be surprising if some windows were mistaken for doors but the photograph below of the 2nd west gallery clearly shows doors beside the porches of the 2nd west gopura (13,) missing from the plan.

The frequency, if not consistency, of these "gaps" in all the plans at least suggests that Banteay Kdei's 2nd enclosure (8) and its peristyle (14) may not have been entirely ornamental but offered informal, oblique pathways between different parts of the temple. These alternative paths would have made possible a dispersion of the temple's traditional rituals and the places to contemplate the divine. This might beconsistent with Buddhism's depersonalized, atheistic, niskala (undifferentiated, non-manifest) absolute, manifested in multiple emanations, everywhere because ultimately nowhere. In other words, the prolixity of optional routes and sadhanas (ritual practices) on the path to an at best nirguna (attribute-less) center which may have found architectural expressed in the "spirit of confusion" at Preah Khan, could have been achieved at Banteay Kdei, simply by more porous circulation patterns.

MONASTIC APSARAS

“HALL OF DANCERS," 3RD ENCLOSURE, BANTEAY KDEI (1181 - 1220)

Dance or drama played an essential role in Hinduism, giving birth to one of the many specialized types of mandapa, the rangamandapa, an open-sided hypostyle pavilion, designed for public performances. As celestial dancers, apsaras no doubt had a key role to play, perhaps like a Greek chorus or corps de ballet, in the religious myths and epics enacted on that stage. At Jayavarman VII’s Buddhist monasteries, like Banteay Kdei, there was still call for a “hall of dancers” and their endowments sponsored hundreds of performers. From their decorations, it seems the dancers were women (males impersonating women may have had to wait for Noh.) Still, the incorporation of women (whose touch was regarded as polluting to a bhikku,) in a Buddhist monastic institution may testify to the Khmers’ relaxed attitude to doctrinal issues. Still how to tell the difference between an apsara and a “daughter of Mara?”

Banteay Kdei's "Hall of Dancers" (6) is not an open-sided, pillared pavilion but fully mural with fenestration and interstitial niches, as well as vaulted shala-roofed aisles, projecting porticos and pediments covering their end-on panjara horseshoe opening. A broad central colonnade with matching north-south transept divides the hall into four small courts encased in double-pillared galleries or corridors. The design seems clearly to derive from the "Hall of Dancers" at Ta Prohm and Preah Khan; it may even owe something to the eastern, hypothetical cruciform structure in Beng Mealea's 3rd enclosure. The southwest porch (at left in the photograph above,) the row of columns behind it and wall constitute the hall's southern aisle; the two pillared courts or atria are adjacent to it, though hidden in shadow. The frieze of niches above the windows presumably once held images of Buddhas diligently effaced by Jayavarman VIII's Hindu fundamentalist crusade, though the apsaras in the niches between the windows were spared as elsewhere.

The most notable difference between the 1st enclosure’s northwest courtyard at Banteay Kdei and its counterpart at Preah Kahn is the absence of the more than twenty ancillary shrines around its periphery, plus a colonnade with hypostyle pavilion. The north (left) and west (right) arms of the temple's axes, pictured here, intersect with the raised northern and western porches and square central sanctuary and shikhara. The rectangular hall, the counterpart on the west of the three-aisle mandapa (9) on the temple's east, with two windows and a door, connects the central shrine and porches with the 1st west gopura (12, out of frame at right,) as well as to this courtyard. Its slight bulge or aisle-less projection is marked by an eave and a kind of aedicular half-story with a standard, barrel-vaulted shala roof above its nave which becomes the dormer of the central shrine's western porch. At the courtyard's center is a balipitha, a square pedestal or socle, with five incised bands topped by a lotus petal frieze, usually used as altars for offerings. As at Preah Khan, it is on a diagonal from the center of the sanctuary to the northwest corner of the 1st enclosure.

NORTHWEST COURTYARD, 1ST ENCLOSURE,

BANTEAY KDEI (1181-1220)

WEST FACE, 2ND ENCLOSURE, BANTEAY KDEI (1181 -1220)

The cruciform 2nd west gopura (13,) pictured above, and the one remaining column of its portico project in front of the long, low western facade of Banteay Kdei's 2nd enclosure (8) at the close of an afternoon. The door to one of the non-axial passageways between enclosures, which characterize this temple, can be seen to the right of its cruciform central chamber and southern porch, near the beginning of the south range of its gallery; its northern counterpart is obscured by the tree trunk at left. The laterite walls surrounding these two openings differ from both the doorframes and surrounding walls; they look pierced or "pounced," suggesting stucco or stone fascia may have been attached to cover the backing. This might indicate the doors were cut into the wall after the completion of the temple, but what then of the aged stone doorframe? Or they might have been repaired or reinforced. The 2nd enclosure’s western gallery has crumbled but, barely visible beyond the anomalous door, behind the tree at right, whose roots may have contributed to the wall's collapse, is one of the four openings into the 2nd enclosure (8) from the 3rd (4,) shown on the site plan, and beyond tts inward-facing, southern peristyle and the collapsed blind (enclosed gallery) of the 2nd enclosure. In the foreground is the elevated causeway leading to the large, 3rd west gopura (15.) At the center is the tower rising above the 2nd west gopura (13,) with three visible aedicular tiers and amalaka. Behind it to the left, is the shikhara of the 1st west gopura (12,) while behind the crumbled 2nd enclosure wall, rise the southwest corner tower of the 1st enclosure (11) and, to its left, the tower of the 1st south gopura.

The bas relief carving at Banteay Kdei is of the same high quality as at Ta Prohm and Preah Khan. The pace of Jayavarman VII's unprecedented building program has been blamed for sometimes shoddy workmanship contributing to its decay. He did not, however, stint on the sculptural embellishment of his monuments where carving covers virtually every inch of wall. This "all-over decoration" has the effect of dematerializing the otherwise monotonous mural surfaces of Khmer architecture's endless galleries, dividing their expanses into bays, separated by pilasters, balusters, floral scrolls, and recesses inhabited by nymphs and temple guardians. The sculpture niches and incised floral panels in this photograph lend a sense of plasticity and even pictorial depth, perhaps even reaching implicitly into the shadowed corridors behind them. Their blind windows with their seemingly superfluous, lathe-turned balusters might induce the paradoxical sensation of seeing into the impenetrable and invisible — the promise of any self-respecting religion or mystery cult.

POLYCHROME BAS RELIEF, BANTEAY KDEI (1181 - 1220)

The usual retinue of Khmer temple servants play their role, inviting visitors inside the galleries, as well as giving Hindu iconography a new Buddhist interpretation. For example, the apsaras framing this baluster window, originally ratnas or jewels stirred up by "The Churning of the Ocean of Milk" to entertain the devas at the top of the kamadhatu or "desire realms" with their celestial music and dance, were easily converted in the Mahayana hierarchies of consciousness to denizens of the rupadhatu or "form realms" who no longer entertained others but delighted in the music of their own being, another example of the Khmers’ seemingly seamless syncretism of Hindu and Buddhist themes.

As these examples of bas relief from Banteay Kdei's 1st enclosure (11) show Jayavarman VII's architects were not reluctant to use polychromy for bold new effects, drawing the eye with swaths of color across the overwhelmingly orthogonal lines of Khmer buildings. Prior to this, different colored stone had been used, if it all, to emphasize specific features such as trim, for example, in the gallery of the 1st enclosure at Phimai. In these later temples, sandstone splashed with rose and verdigris streaks plays against the rectilinear wall divisions, dappling them with light and shade or, more fancifully, the fleeting shapes of celestial nymphs and disembodied spirits.

70

70

74